A visionary performance artist is whipping up a storm at France’s most famous palace.

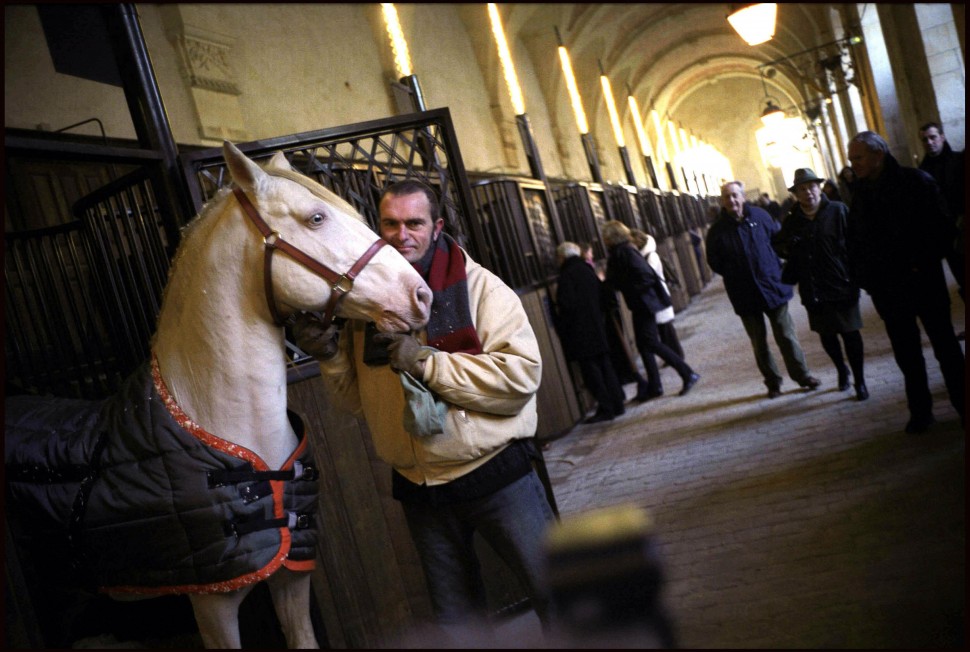

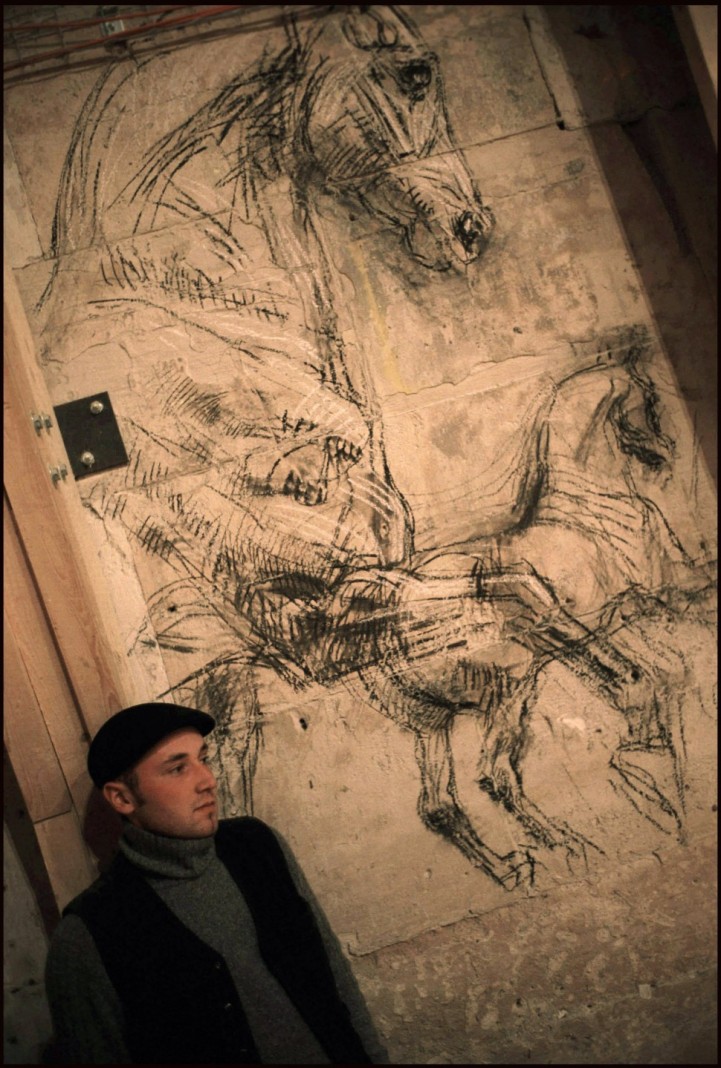

He probably wouldn’t take kindly to being called a “horse whisperer”, but Clément Marty, a tall, gaunt figure in his mid-fifties, with a shaven head and prominent sideburns, who has for years been known simply as Bartabas, is the closest living approximation to the hero of the book of that name and the movie that it inspired. As one of his students puts it: “He may look like one of those scary guys who uses force with the horses, but he doesn’t have a mean streak in him. He is so gentle with them.” This lifetime’s devotion to the animal has led him to invent a new performance-art combining music, dance, drawing, archery and fencing with feats of incredible horsemanship. And now he has been put in charge of what was once a global centre of equine culture — the former royal stables at the Palace of Versailles.

A UNESCO World Heritage Site and scene of the signing of the peace treaty that concluded the First World War, Versailles — as the enormous complex containing the 2,300-room palace and surrounding landscaped park is generically known — is one of France’s premier tourist attractions, luring close on six million visitors a year. It is just a half-hour train ride from Paris’s Gare St. Lazare.

Why Bartabas? For a start, he had already shown that he could be trusted with government largesse: in 1984, at the behest of the then Minister of Culture Jack Lang, the mayor of Aubervilliers, a run-down Paris suburb, had leased him a plot of land for a nominal US$1 [actually one euro, but I can’t do the sign] a year during his lifetime — on which to build Zingaro, the theatre and surrounding caravan encampment that houses his company of performers and some 50 or so horses.

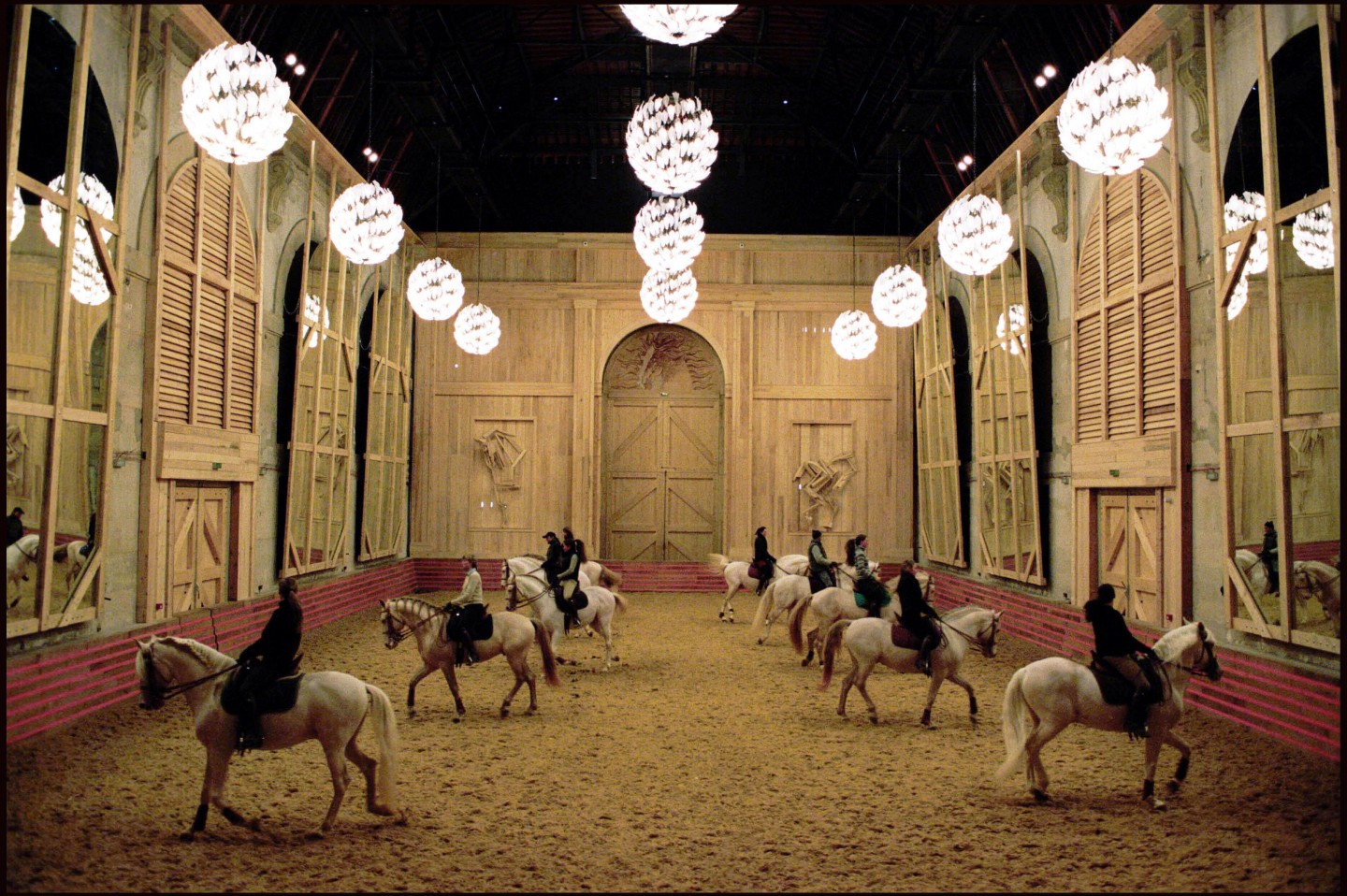

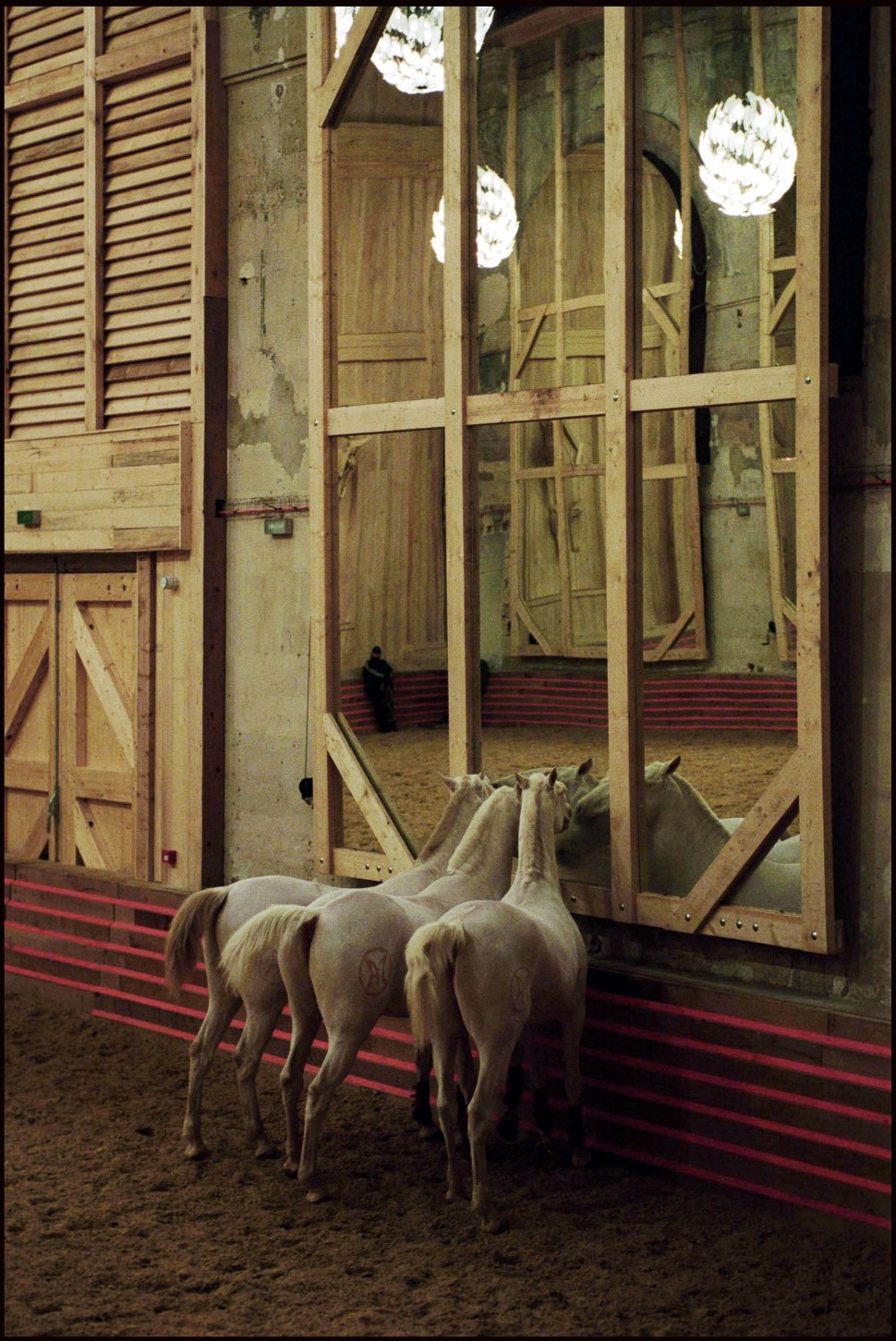

So who better than Bartabas to revive the equine heritage of Versailles, dormant for more than 200 years? With a government grant of US$2.5 million, the Grande Ecurie was renovated to accommodate stabling for some 30 horses, and classrooms. The training arena was pine-panelled and filled with mirrors and chandeliers as well as seating for 600 spectators, whose modest entrance fee covers most of the running costs, the rest coming from sponsorship by the likes of Hermes [grave accent on second “e”].

Bartabas does not regard his pupils as “students” — they are paid a stipend of about US$1,000 a month and provided with free board and lodging and it is hoped that the best of them will graduate to the ranks of full-time company members of Zingaro. Of the 10 (plus four “aspirants”) initially chosen from over 100 applicants for the two-year course, nine are women — and they come from around the world. American Dana Ishli, 19, who dropped out of university to attend, said that she had been excelling at college but “everyone agreed that this was the chance of a lifetime. It’s like a fairy-tale — this is the sort of thing people pay for.”

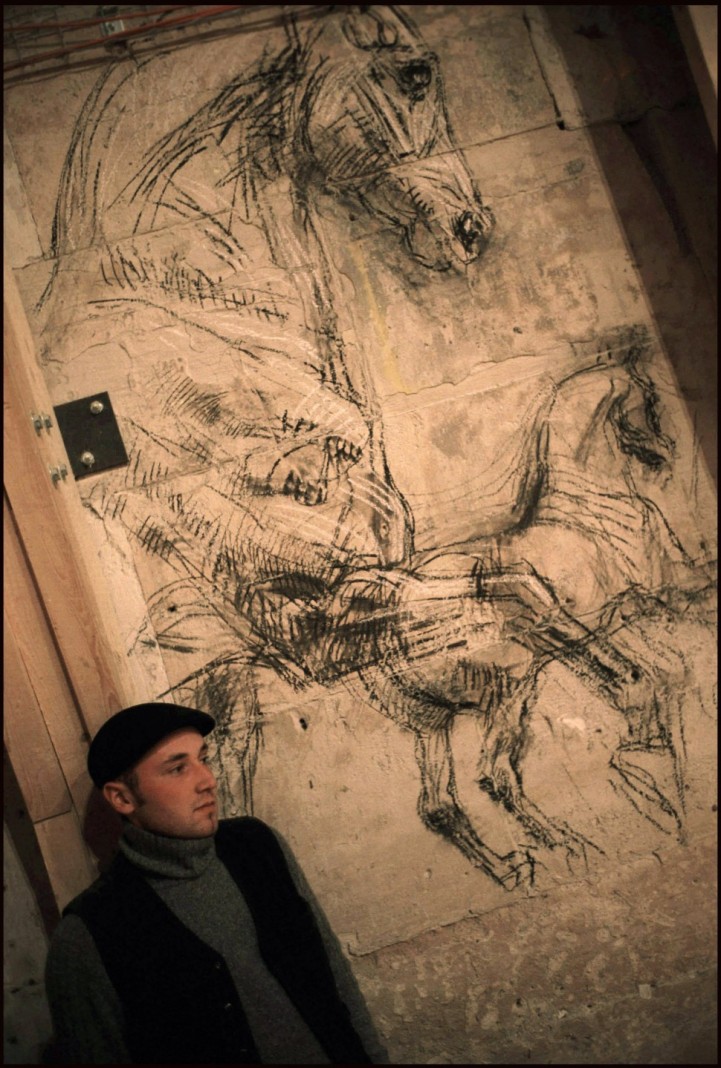

Unlike 30 years ago, when men made up threequarters of his company, Bartabas now employs 85 percent women. He says that the macho prestige of riding a horse has gone — if a man wants to appear powerful, he buys a big car or a plane and leaves the horses to the ladies. In an interview with The Horse magazine, Bartabas explained that apart from horse work, the Academy aimed to train its riders in aspects of the arts.

“Singing makes you confident,” he said, “and when you ride a horse, you want to be confident so that it will have confidence in you.”

Artistic fencing, he said, teaches you “to listen to the other person. It is not like competition fencing, the two of you make choreography, it develops your reflexes. The horse has quicker reflexes than a human so you have to develop that.”

He went on: “People with horses are more thought of as sportsmen, not as artists. We have to develop this sensibility and they will be better on the horse.” He added: “The other idea of the Academy is that all the work will be in public. It is very important for the riders to learn to prepare the horse with people watching.”

My conception of the school,” he said, “is that there is not a time in life when you are learning something and another time when you are making money with that knowledge. You have to be learning all your life. I am still learning. The more I learn on the horse, the less I know.”

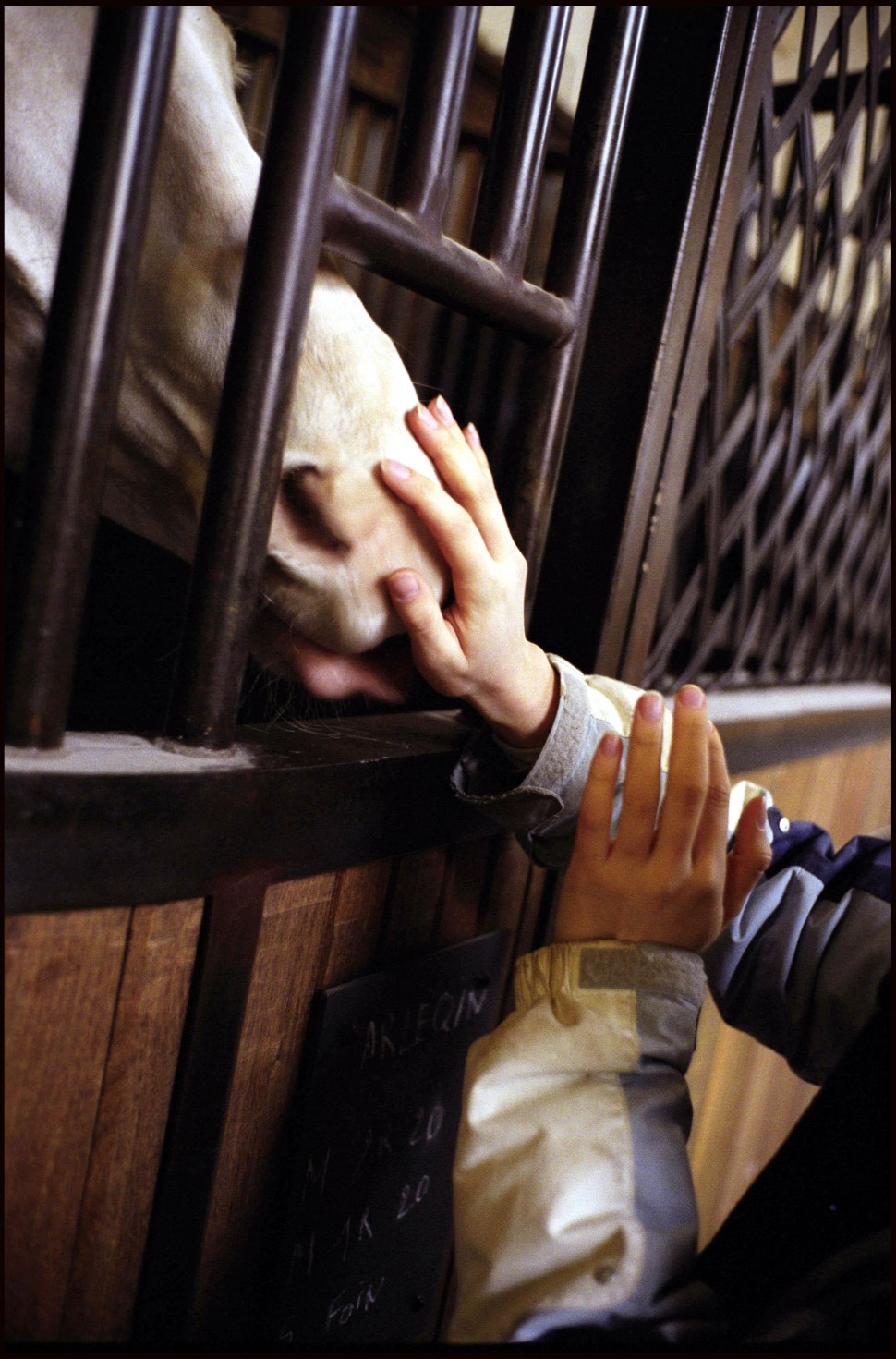

To speak about the relationship between horse and man is to speak about the relationship between people themselves.The way you work a horse is the way you are. If intelligence is the notion of ourselves in the universe, then only the human being has this notion, only the human being knows that they are going to die. The animal doesn’t know that so you can’t speak about intelligence, but you can speak about feeling. The animal has feelings stronger than human beings. If you have a Stradivarius, you can still play it like a butcher — the instrument will respond to what you give it and the horse is the same.”

Stronger feelings than a human being? How does Bartabas feel when a favourite horse dies? “It is worse than having your heart broken,” he says. “Because you lose a part of you — forever.” The man may not be a horse-whisperer, but he is a horse-lover par excellence. Without such a strong emotional bond, it would be impossible to coax the incredible equine performances that have given his shows such a stunning impact throughout the world.