Pioneering new looks for old crafts

![]()

The café is filled with the mid-morning coffee crowd, but Edric Ong stands out easily. There’s a certain air of debonair about him, and besides, there is no missing his quirky rattan hat in grey, orange and crimson.

The multi-pointed hat was designed by Ong as a quirky take on the topi tunjang, a traditional Iban warrior’s hat. To its basic round shape, he added a brim and dyed it in natural colours for subtle funkiness.

The hat is one of Ong’s many innovative designs to update the traditional crafts of the native communities of his home state of Sarawak. It is a fitting symbol of his lifetime mission of reviving Malaysia’s indigenous arts.

The hat was designed for the annual Santa Fe International Folk Art Market, which aims to celebrate and preserve living folk art traditions and create economic opportunities for the artists worldwide.

“It became a show-stopper as people stopped to ask where they could get the hat. It’s a good ice-breaker,” Ong says. “In every show, you are an ambassador for the country.”

In his tireless mission as ambassador for these old arts, Ong says crafts don’t have to stay stagnant as the same techniques can be used to create new products to appeal to the contemporary market in Malaysia and the world.

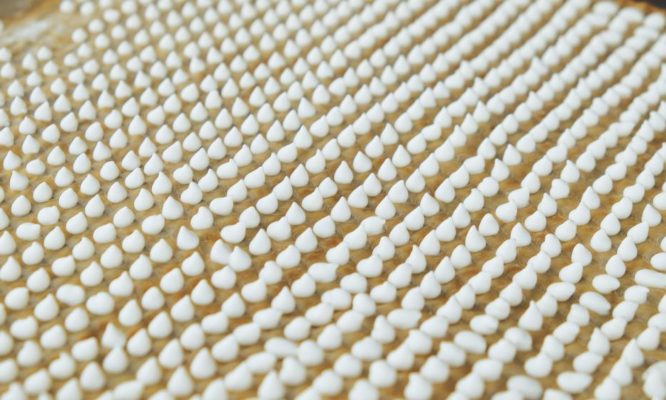

For instance, Iban woven items are now used to make bento boxes for Japan or storage baskets for Australia, and native rattan creations and beadings have been turned into buttons that have become a hit in the U.S.

Innovation in craft is the ethos behind Ong’s dizzying range of projects. On some days, he is a fashion designer who pioneers new uses for old crafts, and uses fashion to promote them. On other days, he’s a hands-on researcher working with natural dyes to find new ways to update old techniques.

Yet on other days, he is jetting around the globe to promote heritage crafts, the best of which can hold their own among the best in the world. Malaysian weaving and fine basketry are second to none, he said.

Ong’s three decades of work have won him recognition as one of Malaysia’s pioneering defenders of heritage crafts. Along with roles such as president of Society Atelier Sarawak, he has picked up so many awards that even he might find it hard to remember all of them.

The most recent was at the 2016 Mercedes-Benz Stylo Asia Fashion Festival, where he won the Stylo Global Fashion Influencer Asia 2016 award presented to fashion icons who have put Malaysia on the international map.

Today, Ong’s days are filled with perusing the finest details of handicraft, but his career actually began with much bigger structures. He was an architect for three decades, working on landmarks such as the Sarawak Cultural Village.

But to him, architecture was never just about buildings. It’s about designing an entire experience, and hence, he did not stop at just designing the outward structure but also delved into the finest details of the finishings and furniture.

“As an architect, I was interested in all aspects of the design, from outside to the inside. These should all be designed, including the furniture to accessories. Sometimes, people say, you are a control freak!” he says. “But otherwise, it will not look right.”

He found Sarawak to be a treasure trove of traditional design for his architectural works, and there began his journey to preserve these heritage arts.

A soft-spoken man with an infectious grin, Ong’s big project this year is co-curating the exhibition and symposium entitled World Ikat Textiles, Ties that Bind in the prestigious Brunei Gallery at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London.

Ikat is a tie-dyeing technique that is still practised in five continents, with some of the most beautiful ikat textiles made by Iban weavers in Sarawak using natural dyes obtained from the bounty of the rainforest.

With so much on his plate, Ong has put his architectural practice on the backburner to focus on indigenous crafts, fully aware though that he’s fighting an uphill battle to keep this old heritage from disappearing.

“The education system has detached the younger generation from their home, so it’s a big challenge,” he says.

He notes that crafts traditionally done by women such as textile or basket-weaving have a better chance of survival, while those done by men like wood-carving are much harder to revive. Many of the younger men who used to make wood carvings have now gone to work in timber camps.

Yet, he says it is imperative to preserve this precious heritage of the country. “Craft is culture, and culture is people. Without culture, you have lost your identity,” he says. “It’s important to preserve our culture and heritage because that defines our identity as a people.”