An artisan ensures the game of gasing, once a popular pastime, survives the test of time

In one graceful yet controlled motion, Rimy Azizi Abdul Karim flings the spinning top to the ground, where it lands with a whip-like crack before gyrating fluidly for the next few minutes. A well-made gasing can spin up to two hours, he tells me.

Top spinning, whose Malay-language name was derived from kayu (wood) and pusing (spin), is believed to have been brought to the Malay Archipelago courtesy of Middle Eastern traders. Quickly picked up as a post-rice harvest men’s game, the advent of video games and other modern distractions has threatened its popularity as a leisurely pursuit, but not if artisans like Rimy can help it.

Rimy hails from several generations of gasing makers. After catching the gasing bug from his father Abdul Karim, he travelled nationwide, including to the Malay heartland of the East Coast and the southern state of Johor, to apprentice with the best gurus in the trade – eight, no less. His passion for gasing deepened as he realised “it is a beautiful game, rich in history and stories”.

In Malaysia alone, over 100 types of gasing are in existence. Even from Rimy’s prized personal collection, one can discern the richness of cultural information in each gasing’s characteristics, from name and shape to type of wood. Gasing jantung is derived from the shape of a banana heart, a popular ingredient in Malay cooking. Gasing talam dua muka, a dual-faced top, refers to a famous Malay proverb about the treacherous nature of humans, while lang laut is inspired by the sea.

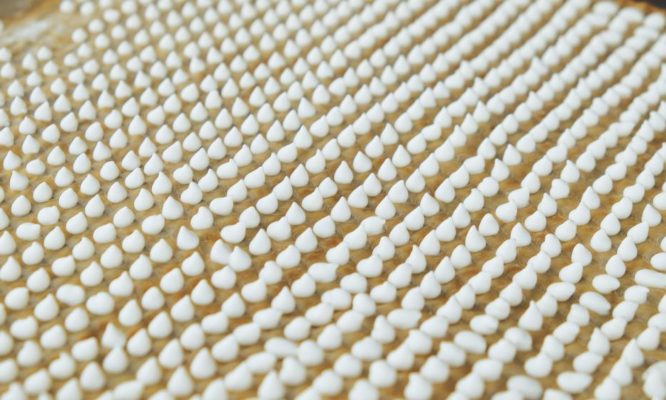

Making a good gasing begins with the search for hard, malleable (liat) wood; cengal, ciku and mangrove are popular species. Traditionally, the materials were obtained from rivers and forests but the scarcity and high cost of raw wood prompted Rimy and other gasing-makers to fall on an unlikely source: recycling. Wooden beams from old kampung houses are sufficiently dry and seasoned; the cost is cheaper by 40 percent as well. Using an iron axe, the wood is cut into 15cm cubes and dried out before each block is hand-hewn into a gasing’s curvy shape. A spinning machine is used to drill a nail or axis into the centre; the extra weight prolongs the spin, and then it is chiselled to immaculate smoothness before being sandpapered and spray-painted for a shiny finish.

On a good day, Rimy can make up to 20 in his top production workshop in Kampung Cheng. Since going full-time in 2007, his company, Gasing Lagenda Enterprise, has worked closely with the Malaysian Handicraft Development Corporation (Kraftangan Malaysia) to produces tops as gifts and souvenirs as well as for competitive use. Melaka is renowned for gasing pangkah, a highly skilled game where contestants smash their spinning tops against those spun by rival team members. Apart from making tops for his own company, Rimy runs short gasing-making courses and performs demonstrations in hopes of generating public interest, and eventually, training successors. His biggest coup to date is a 24-hour gasing competition in 2012 that made it to the Malaysian Book of Records.

Rimy occasionally employs acrobatic tricks to attract crowds. I’m caught between amusement, admiration and alarm of injury as he juggles between using his forehead and finger as a spinning pad. Gimmicky or otherwise, his showmanship has impressed at least two members of the younger generation who are his target audience: his children, Adam Tuah, 3, and Nor Umairah, 5, are pretty mean throwers.

“I don’t want spinning tops to end up in a museum one day. My biggest dream is for the game to go beyond ceremonial use, and make a comeback in the day-to-day lives of ordinary people,” he added.

Rimy Azizi Abdul Karim,

Gasing Lagenda

833-1, Batu 5 ¾, Kampung Cheng Melaka

+6017 613 4644