Audiences and appetites for Singaporean cinema have grown, but a strong pool of talent with the right training is needed to stay the course, says filmmaker Wee Li Lin.

Photography courtesy of Singapore Tourism Board

When you think of Singaporean films, you’re likely to recall major hits like Ah Boys to Men and Army Daze. But look deeper and you’ll find a rich pool of talented filmmakers who are raising the profile of the Singaporean film scene on local and international levels.

Among them is Wee Li Lin, an established filmmaker with several short and feature films under her belt, including Norman In The Air (1997), Gone Shopping (2007) and Autograph Book (2015), which was the first-ever Singaporean film selected for the prestigious Tribeca Film Festival in New York. She also received the honorary award at the Singapore Short Film Awards in 2011 for her outstanding contribution to Singapore’s short film scene.

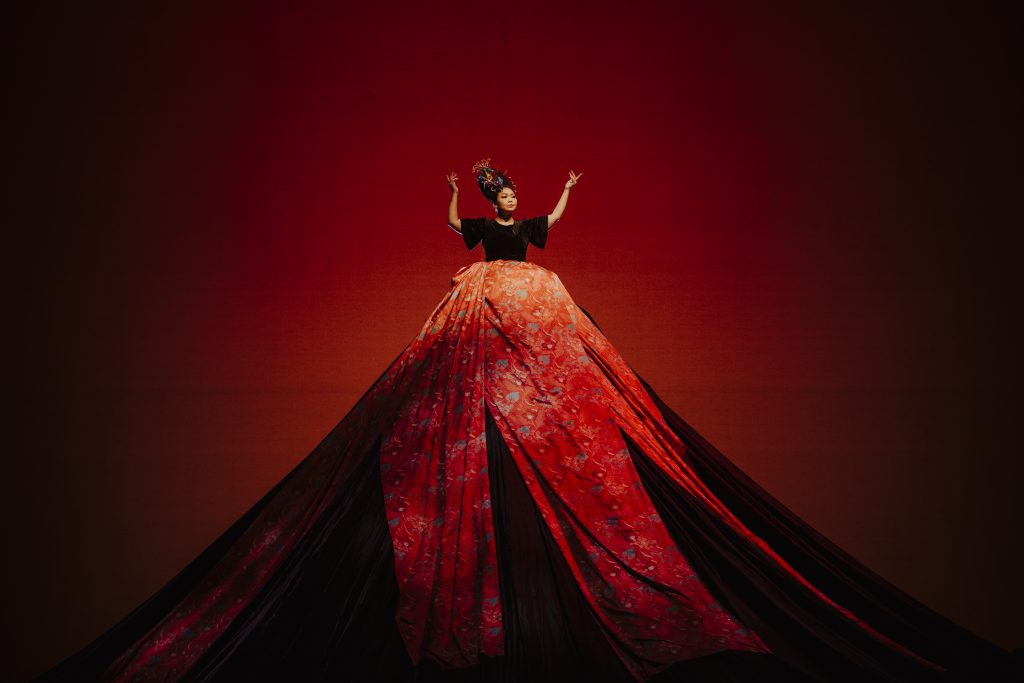

Her latest effort saw her work with Viddsee to conceptualise five connected short films for the Singapore Tourism Board’s campaign to woo travellers who enjoy being immersed in arts. The short films were then directed by Li Lin (Interwoven), Sabrina Poon (In Generations To Come), Sun Ji (Alone Not Alone), Tariq Mansor (Walls) and Don Aravind (2002) – all Singaporean filmmakers.

What led you to become a filmmaker?

I always knew I wanted to do something creative – painting, photography and writing. When I took an experimental film class in university, I realised filmmaking captured all my interests, and I enjoyed bringing characters that I felt for to life. Eventually I was drawn into narrative filmmaking and not so much experimental film that my uni was known for. I did a semester at NYU Tisch in this programme called ‘Sight and Sound’ and that experience really cemented my commitment to filmmaking and I decided I was going to pursue this wholeheartedly.

What stories do you want to see more of coming out from local filmmakers?

It would be exciting to see more female-driven stories being told and films about the female gaze. I would also like to see more Singapore content in ‘Singlish’ and in mixed languages as I feel like our native tongue is eclectic and unique. I would encourage filmmakers to have courage to say what you need to say and resist the urge to self-censor.

Having witnessed the local filmmaking scene develop since your first film in 1997, how have attitudes and the approach of local filmmakers towards the stories they tell changed over the years?

It hasn’t changed in the sense that there are two camps. On one hand are the commercial films that are driven by a certain elusive formula that everyone is hoping to find. On the other hand, you have films that are very indie and seek to stir controversy.

Both camps have been growing because there is now more funding, awareness and support for Singapore filmmakers. But there is some middle ground that’s been missing for a while – the kind of narrative indie films that aren’t geared towards the festival circuit but don’t fall into commercial stereotypes either.

Maybe television is that middle ground, but because of existing conservative thoughts within the TV industry and the self-censorship that we impose, there needs to be more depth and leeway for the way the characters communicate in Singapore.

But there are encouraging things happening now. Over the years, we’ve seen more films coming out from female filmmakers and Malay and Indian filmmakers telling their stories in another language; they really shine and provide more representation. And also, audiences and appetites have grown for Singaporean cinema – and that’s helped by a number of films creating a big impact internationally. That’s an incredibly encouraging achievement that our city-state can be proud of.

What would you like to see happen in the local industry in the next five to 10 years?

I would like to see growth in the acting industry – more classes, courses and even degrees solely focused on acting for film and TV should be made available; we have that rigour for acting in theatre, but not for film and TV. We can’t really have an industry without a strong pool of actors with the right training – that would be something vital over the next 10 years if we want the local film industry to thrive.

What is the inspiration behind Interwoven?

I wanted to tell a story of an everyday person, who has everyday responsibilities, who felt boxed in a role. In Interwoven, the character Noor is an ‘auntie’ who is a mom and shop owner, who wants to be recognised as a creative person. Through the encounters Noor has with culture shapers like Santha Bhaskar, Ivan Heng and Zul Othman, she begins to gain confidence and inspiration to embrace her wholeness, which is that she can be a mother, a shop owner and an artist. The film is about courage, passion and family.

What are the values or messages that you hope to send to viewers through your films?

I’ve always been interested in characters who are trying to find their place in society, and making films that expose a dark or bright side of humanity. One such inspiration is Mike Leigh’s Happy Go Lucky, which was a nuanced, funny, and heartfelt film. If I could aspire to some of that, I’d be pretty pleased.

For someone who isn’t familiar with works by Singaporean filmmakers, what are the must-watch films or shorts that you’d recommend them to watch?

I’d recommend Ah Ma by Anthony Chen, Hock Hiap Leong by Royston Tan, Moveable Feast by Sandi Tan, Jasmine Ng and Kelvin Tong, CA$H by Tan Wei Ting, I Believe by Leroy Lim, All The Lines Flow Out by Charles Lim Yi Yong, Sink by Kirsten Tan, and You Idiot by Kris Ong. I would recommend my own short, Areola Borealis, which is based on the true story of how I loaned my bra to my friend on the night of her wedding dinner. The film talks about race, repression and love.