More than just a cultural tradition, the spectacular lion dance has evolved to become a sport-oriented activity.

Words Carolyn Hong Photography SooPhye

If there’s one sound that tells you it’s the Lunar New Year in Malaysia, it’s the deafening clash of cymbals and deep rhythmic pounding of drums that accompany the lion dance. This acrobatic and joyful spectacle is an integral part of the festivities, not to be missed.

The lion dance migrated to Malaysia over a century ago with Chinese emigrants, but since then, it has evolved to have its own distinct identity. A heady spectacle of sights and sounds that will leave your heart pounding, it was listed as a national cultural heritage of Malaysia in 2007.

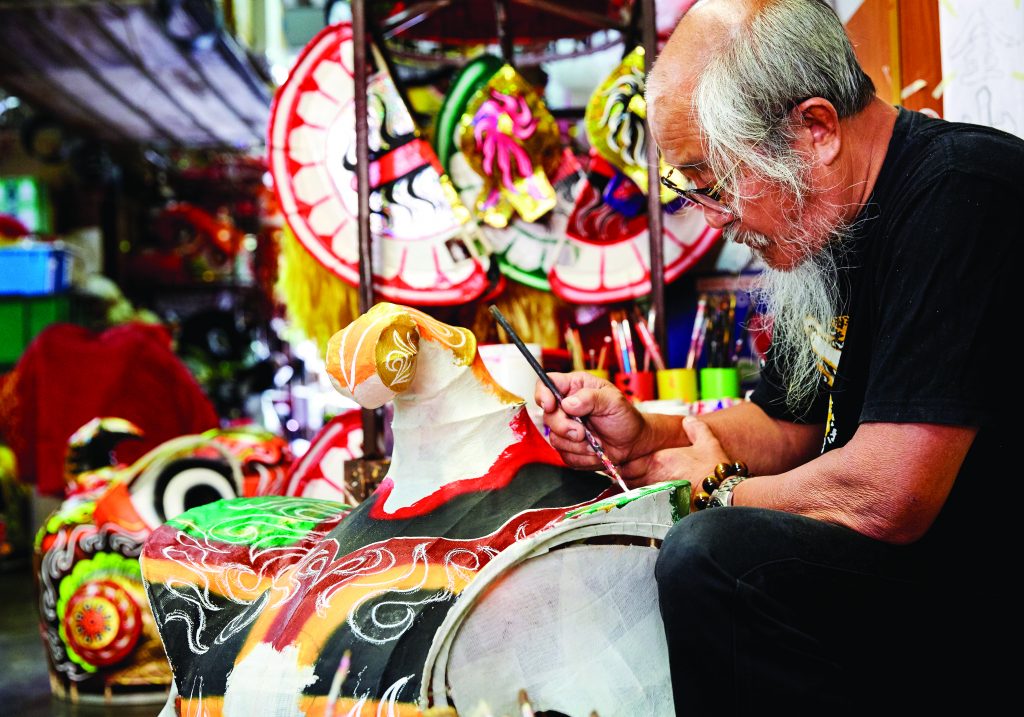

“The lion dance of today is different from the past,” says lion dance master Siow Ho Phiew, who teaches the art form and owns an acclaimed workshop, Wan Seng Hang Dragon & Lion Arts, which makes lion dance costumes. Siow is widely acknowledged as a master of his craft, having received an award for his work from the Malaysian Handicraft Development Board in 2011.

In Malaysia, the lion dance is most often performed during the Lunar New Year, but it also makes an appearance at important events such as the opening of a new business to welcome important guests, at auspicious celebrations, and in competitions.

Draped in an elaborate costume, two dancers play the lion – one as the head, the other the tail. Accompanied by the cymbals and drums, the dancers prance to the beat as they mimic the movements of a lion as it wakes, eats and gambols, while performing different stories for different occasions.

The lion dance became popular in the 1970s in Malaysia, with master teachers from China coming over to train young enthusiasts. The art form climbed from height to height, with Malaysian lion dancers now regarded as among the world’s best, most daring and acrobatic.

In Malaysia, the lion dance has evolved beyond being a Chinese cultural art form into an acrobatic sport participated by people of all races and cultures. Siow, who has taught many non-Chinese Malaysians, says the lion dance is as much about etiquette, grace and discipline as it is about culture.

His workshop, set up in 1986 to make lion costumes, makes about 300 elaborate costumes a year, highly sought for their intricate work and creativity.

Siow, 64, has been steeped in the art form since he was 17 years old. Over the decades, he has deepened his skills and knowledge, and still teaches today. He often spends his days in the cramped workshop, and when we met him, he was polishing glass eyes to be fitted into the lions’ heads.

Each head is handmade, beginning with rattan bent into a frame. Paper is wrapped around the frame and painted with intricate designs. The final product is a sight to behold – a fearsome lion’s head with eyes that blink and a mouth that moves. Thick fur and other adornments add to the mystique.

There’s surprisingly a lot that can be tweaked to make the heads unique, from colours and patterns to individual flourishes. The colours may be the corporate colours of a customer, and the design may account for requests to incorporate specific symbols.

The lion dance in Malaysia, as with the rest of Southeast Asia, is the Southern lion dance from Guangdong province in China. It has at least two styles, both of which are practised in Malaysia. The Northern lion dance is performed by male and female lions for the imperial court, with a shaggier costume. It is rarely performed in Malaysia.

Traditionally, the Southern lion’s head comes in specific colours, drawing from the symbolism of historical characters of the Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE). The yellow lion with a white beard and colourful tail represents Liu Bei, the eldest brother in the novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms, the white beard signifying his elderly age. His brother Guan Gong is symbolised by a red lion with a black beard, with the black beard symbolising youth. These traditional colour combinations aren’t often used today except for cultural events depicting traditional stories.

Today, there are lions in all sorts of colours: lions in corporate blues, startlingly purple ones, shocking pink lions and even those adorned with LED lights. For competitions, red-and-gold with a bushy white fur trim is still the most popular choice for its striking appearance. The lions’ heads come in different sizes, with the smallest made to fit a child of nine to 10 years old.

Siow’s busy workshop makes lion costumes for customers from as far as Hong Kong and China. They are sought after for their fine work, and also because Malaysian-made lion heads have evolved to have a distinct identity.

In the distant past, during the days of the imperial dynasties in China, Siow said the movements of the lion dance often carried hidden meanings. Even the classic move of eating vegetables hid a political meaning as the word for vegetable in Chinese sounds similar to the name of a disliked imperial ruler.

Today, the symbolism has changed, of course, even if the movements remain identical. The lion dance is performed to usher in prosperity and chase away bad fortune. The lion performs different moves, depending on the occasion. Typically, the lion is depicted as bold in seeking new experiences but cautious in studying his surroundings.

In many performances, the lion dance still typically includes a segment where the lion clambers and jumps energetically to grab a lettuce dangled high above. The act of climbing is symbolic of reaching for greater heights, and the lettuce is a symbol for prosperity as its name in Chinese also sounds like creating wealth. The ‘eating’ of the lettuce and the scattering of the shredded vegetable symbolise the spreading of prosperity.

During the Lunar New Year, the lion also peels Mandarin oranges, a symbol for gold, as well as arranges the peeled oranges, pomelo or lettuce to present to the host as a symbol of good fortune.

Siow says on specific occasions, the lion may perform more intricate tasks. For instance, at the opening of a textile shop, it may cut a piece of cloth into a shape of an outfit. “There are other stories as well, such as the lion chasing away a snake or scorpion which symbolises bad fortune,” he says.

For competitions, the performance may depict a lion climbing a high mountain in search of medicinal herbs or playing with water, to enable the performers to show off their acrobatic skills in dancing on high poles and across water.

Siow says the skills level in Malaysia grew exponentially from the 1980s, when lion dance competitions were introduced. Malaysians organised the first international lion dance invitational in 1983, and since then, different troupes have vied for the top spot in the annual championships.

“The performers worked hard to improve their skills, and they also learned from each other,” Siow said. He has come up with many popular new moves for his students, requiring them to undertake daring leaps and twirls on high poles.

“If it’s a cultural event, it’s just for one community, but as a sport, everyone can take part.” As such, Siow says, old cultural taboos have vanished. If previously, women did not participate in the lion dance, it’s now common to find female performers. There was once even an all-woman troupe in Malaysia.

“It’s all in here,” said Siow, tapping his forehead. “If you are doing something good with good intentions, then it is good. There are no taboos.”