Appreciating sound in a film.

Photography SooPhye

Three men are waiting at a train station in the middle of nowhere. There’s scant dialogue, the scene driven by the sounds of a somnolent afternoon of a hot day: the chirping of birds, boots scraping against dusty floorboards, cracking knuckles and a buzzing fly. This is Sergio Leone’s classic Once Upon a Time in the West, its magnificent 10-minute opening scene shaped by immaculate sound design. The scene ends with the roar of an approaching train, and the strains of a harmonica introduces the man they are waiting for.

“It is one of my favourite scenes with almost no dialogue but very good sound design,” enthuses Zahir Omar, a Malaysian filmmaker. “Sound can really shape a film and give it an added dimension. I think not enough attention is given to sound design.”

Compared to directors, actors and the visual components of a film, sound may not be the obvious superstars of filmmaking, but it is one of its most important elements. Good sound design in films is such an essential part of the experience that we take it for granted. If you’ve ever had to watch a clip of a movie without the sound effects or background music, you’d immediately sense its absence. It’s a disembodying experience.

When it came to his debut film, Fly by Night, a crime thriller set in Kuala Lumpur, Zahir paid attention to the sound production. Together with his sound designer and music director, they spent four months on sound design, a luxury for an indie film, but Zahir was determined to get it right.

One of his favourite scenes in the film is set in the interrogation room. The ventilator fan gives off a low hum and a clock ticks in the background. The sense of humidity amplifies the emotions of the character in custody – the anxiety, fear and helplessness.

Used effectively, sound is a powerful emotional tool. It can change the mood of a scene and set the pace of the plot. It can make us laugh or make us scared. A horror film would not be as impactful without the accompanying creepy sounds.

“Sound is a great story-telling tool. It can create a great emotional experience for the audience. Without it, the audience will lose a big portion of the film’s experience,” says Axle Kith Cheeng, a freelance sound designer.

In 2012, she won a prestigious industry Golden Reel award for sound editing by a student filmmaker for the stop-motion short film Head over Heels. The Oscar-nominated film, directed by fellow National Film and Television School student Timothy Reckart, is about a married couple that has grown apart and is depicted as living in opposite sides of a floating house – one is grounded while the other’s world is upside down.

“When both characters are in the house, we can feel their mutual hostility with the chaotic noises happening inside the house. The noise from Madge’s vacuum and Walter’s TV static suggest a very uncomfortable house,” Cheeng explained.

When the house is grounded and Madge ventures out of it to explore the world by herself, she looks back at the house and realises that she misses Walter. “In this scene, the ambience is very quiet with some cold wind to suggest her loneliness, and her footsteps sound mushy to suggest her heartache. The foley work here is very detailed and exaggerated, so we can feel her emotions,” said Cheeng.

Foley is the reproduction of everyday sounds added to a film in post-production and can be anything from footsteps on creaky boards to the sound of laundry flapping in the wind. “I love doing foley and there is a lot of foley work put into Head over Heels. The film has no dialogue. That’s my forte, making a world just with sound.”

When it came to designing worlds, Cheeng had her work cut out for her on an award-winning animation series called Insectibles. “I had to design the movement sounds for a snail, a wasp and a caterpillar,” she said.

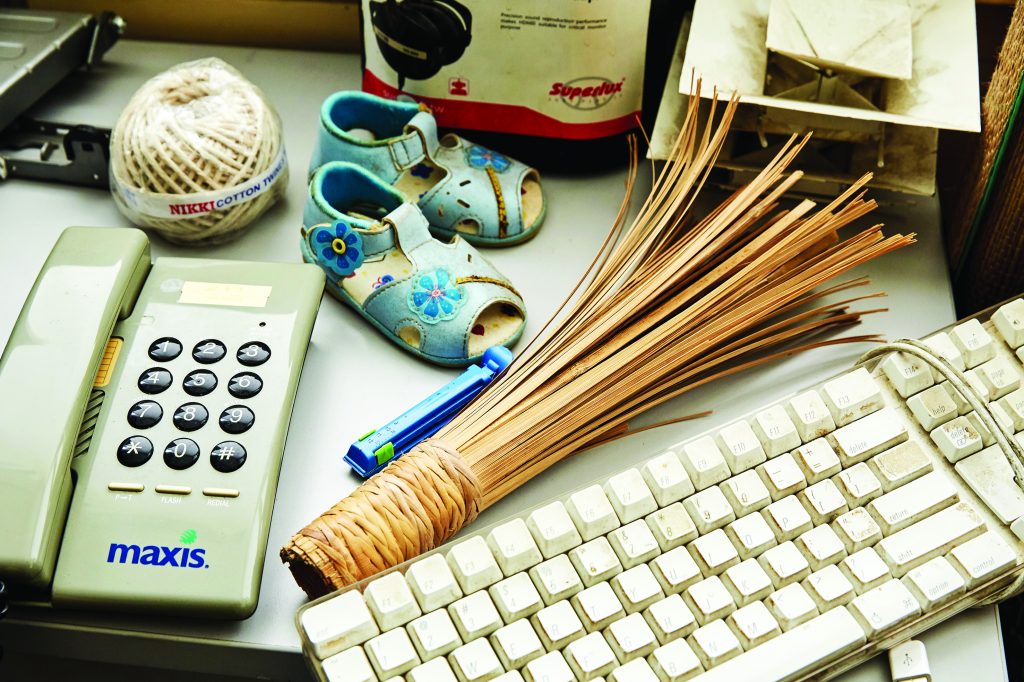

For the snail, she crushed oranges to get the squishy and slimy sounds of a snail on the move. The caterpillar’s movement was reproduced with a rubber swim cap and the wasp was two pieces of raffia string tied to foil and flapped in time with the insect’s wing movements.

Creating the right sounds is not a simple or trivial task, but sound designers often get the short shrift when it comes to time and budget, especially in low-budget productions. “Sound is still not a priority in film production; hence it is left to the very last stage of filmmaking where everything needs to be fixed in a short period of time,” said Cheeng.

Georgina Tan, the managing director of film and media group Supernova Media agreed that budget is a contributing factor in the quality of sound in films. “I would say it is the biggest challenge,” she said in an email interview.

“Sadly, when we receive a film, it is always when the budget is almost finished, and they are left with so little to cope with costs,” said Tan, whose company works with local and international productions.

“The correct treatment and layers can transform a seemingly bland offering into a visually stunning piece. The right sound can create an impactful sense of whatever the director or film creator had envisioned.”

The sound design team at Supernova just wrapped up work on Astro Shaw and HBO Asia’s adaptation of Tan Twan Eng’s The Garden of Evening Mists, a film set in post-World War II British Malaya. With this film, they had a proper budget and time to recreate the sounds of that era, including of Japanese fighter planes and weapons. “Anything that is not current can be challenging. Not only do you have to simulate sounds that are relevant to that time period, but as with every film that we do, there are special tricks,” said Tan.

The trick of good sound design is to make it seamless and smooth, said Cheeng. “Because it is so subtle, you won’t notice it. But if it is missing, you will feel a kind of emptiness. As a good sound designer, we know when we have done a good job when the audience is not jolted out of their film experience because of the sound.”