The story of Sybil Kathigasu is one of courage and conviction under extreme circumstances.

Today, Papan in the northern state of Perak looks very much like the small towns that dot the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia. But during the Japanese occupation in the Second World War, it was a key nerve point for the underground resistance.

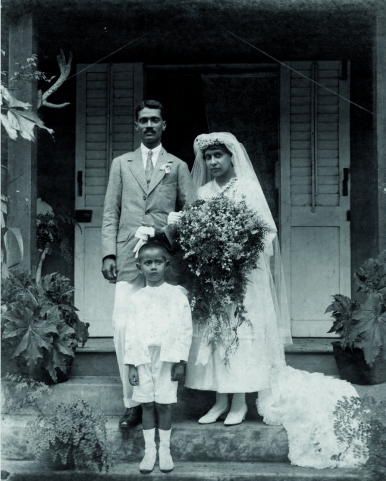

Sybil Kathigasu, wife, mother, nurse and later war hero, moved to Papan just days before Japanese troops marched into Perak’s capital of Ipoh, where she and her husband, Abdon Clement Kathigasu, a doctor, had been operating a clinic.

The couple helped guerrillas hiding in the Malayan jungles just beyond Papan with food, medicine and information, and treated their injuries. The couple kept a shortwave radio concealed, tuning into forbidden broadcasts.

As food became scarce and inflation soared, Sybil worked to keep her family and friends fed through a combination of relentless effort and resourcefulness. Heeding the call for food security by the Japanese occupiers, she planted vegetables and added a bamboo fence, ostensibly to protect the vegetable plot.

The house the couple lived in became a calling point for injured Malayan People's Anti-Japanese Army guerrillas who were treated in secret. The house itself was adapted ingeniously; the tall bamboo fence helped people approach the house unseen from the main street, and a small room at the back was fashioned into an operating theatre.

The couple's efforts put them at risk. The Japanese ruled in a climate of fear and sought information through a network of informants. Stories about their brutality were also spreading fast.

In 1943, Sybil and her husband were betrayed to the Kempeitai, the military police of the Japanese Imperial army. First her husband and later Sybil were arrested, accused of treason for collaborating with anti-Japanese guerrillas, a crime punishable by death.

In the months that followed, they suffered barbaric torture as their interrogators sought to extract information from them. In her unfinished autobiography, No Dram of Mercy, written after the end of the war, Sybil talks about her torture.

“They seemed desirous of battering the truth out of my body. Each unsatisfactory answer I gave – and they were all unsatisfactory – was followed by a dose of intense physical pain, administered in varying quantities and many different forms,” she writes.

“They would run needles into my fingertips below the nail, while my hands were held firmly, flat on the table; they heated iron bars on a charcoal brazier and applied them to my legs and back; they ran a stick between the second and third fingers of both my hands, squeezing my fingers together and holding them firmly in the air while two men hung from the ends of the cane, making a see-saw of my hands and tearing the flesh between my fingers,” she continues.

Sybil endured spells in solitary confinement, was forced to watch her husband being beaten, and in one particularly low point, her daughter Dawn was the pawn in a Japanese official's sadistic game of mental torture. He threatened to lower the seven-year-old whom he had suspended from a tree into a fire below to make Sybil talk. Mother and daughter were saved by the intervention of another officer.

The Japanese found Sybil guilty of treason and sentenced her to life imprisonment, but by then the war was already nearing its end. In poor health, Sybil was freed in August 1945 and was later brought to Britain for treatment. While there, she underwent numerous treatments but she never fully recovered. She succumbed to complications from the injuries she sustained on 12 June 1948.

Sybil, born Sybil Daly on 3 September 1899 to an Irish-European planter and a French-Eurasian midwife in Medan on the island of Sumatra in today's Indonesia, was awarded the George Medal, the highest British honour for bravery, in 1947.

Apa Dosaku: The Sybil Kathigasu Story is showing onboard.