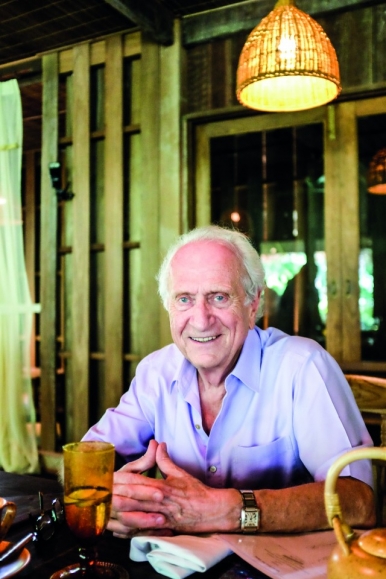

Legendary French chef Michel Roux waxes lyrical over a world of flavours

Surveying a feast of traditional Malaysian favourites prepared for him, Chef Michel Roux nods in approval. The revered Frenchman, credited for revolutionising England’s culinary landscape half a century ago, bites into a skewer of beef satay, takes a spoonful of steamed fish custard known as otak-otak, and nibbles at a bowl of piquant, lightly spicy glass noodles.

“When I’m in this part of the world, I like to eat the local food – food of the street, that’s what I love. That’s how the palate develops better,” Roux says, commanding the rapt attention of a table of lunchtime companions at The Gulai House, a restaurant at The Datai luxury resort on Malaysia’s northern Langkawi island.

Roux speaks with the measured, authoritative precision of one of today’s most extolled living chefs. He and his brother Albert, raised in a family of charcutiers, ascended to fame after they moved from Paris to London and opened their first restaurant, Le Gavroche, in 1967. Their second venue, The Waterside Inn in Berkshire, was launched five years later; both establishments have earned the highest accolade of three Michelin stars, with The Waterside Inn becoming the first restaurant outside France to retain all three stars for at least 25 years. Their clientele spans a star-studded list that has stretched from Britain’s royal family to Charlie Chaplin, Ava Gardner and Sophia Loren.

More crucially, the Roux brothers have been hailed for invigorating London’s gastronomic scene with their flair and finesse, pulling the city from its so-called ‘dark ages’ of eating out. Over the decades, many of Britain’s most recognised chefs have trained in the Roux kitchens, including Gordon Ramsay, Marcus Wareing and Marco Pierre White.

Turning 75 this year, Roux now resides in Switzerland while his son and nephew helm the family’s flagship restaurants. But he remains active in travelling the globe, with his reputation and experience highly coveted for culinary events. At The Datai, he was cooking in Malaysia for the first time, dazzling his fans this past February with a sold-out three-night showcase of haute cuisine.

“The appreciation for food has changed a lot around the world. What I love is that people are ready to try food that they never knew about, and they seem to enjoy it,” Roux reflects.

“All cuisines have something different to offer. I like Thai food. I like Vietnamese food – it’s clean, it’s healthy, it’s simple. I love Indian dal. And certainly I love Chinese,” he adds. “I’m not here long enough, but if I were, I would ask the Malaysian cooks to prepare for me the meals of their families, because that is what we should eat to have a true picture.”

He adds, with a twinkle in his eyes: “I lived in Britain for over 40 years, so I’m not like a Frenchman when it comes to spices. One of my daughters, she can’t take spicy food, she just can’t take it. I told her, you’re going to die without knowing what life is about.”

For Roux, authenticity matters. The dishes he curated at The Datai featured time-honoured French techniques that brought out the best in fine-dining flavours and textures. Guests began the evening with canapes of gougeres (baked choux pastry with cheese) and smoked salmon and scrambled eggs on brioche buns, paired with Champagne from Roux’s own label, served in a spectacular poolside setting surrounded by the rainforest.

Dinner proved a parade of pleasure after pleasure. A terrine of foie gras, chicken breast and pistachios prepared with ratafia fortified wine yielded a ravishing melt-in-the-mouth richness. Poached sole was compellingly matched with broad bean mousse and sorrel sauce. Pan-fried lobster with white port sauce and ginger-flavoured vegetable julienne had diners swooning with its succulent, briny dimensions; one Australian guest declared it “the best lobster I’ve had in my life.” The duck with confit lemon – carved by the table – was divine; no surprise, since the fowl was of the prestigious Challandais breed. The meal ended on a high with a smooth yoghurt dessert coupled with a lime marshmallow and raspberries.

Roux stresses that he’s opposed to fusion fare, insisting that most chefs lack the skill to marry the cuisines of different countries and continents. He lists Japanese-born Australian chef Tetsuya Wakuda as one of the rare exceptions. He also disavows molecular gastronomy, saying the chemical transformation of ingredients to concoct eye-catching components is “not cooking”.

“Traditional French cooking is my main thing. Some Asian herbs and vegetables I can incorporate in my meat or fish dishes. But I don’t push it too much. I want a clear definition of the product,” he explains. “In French cooking, if you start to overdo it, you lose your French food.”

“But I like other European food very much too. For me, going back to Europe, Italian food is the last bastion of gastronomy. Between the risotto, the pastas and the pizzas, Italian food for me is the best food in Europe, with the best produce. But it doesn’t stop me from eating some good Spanish food if I feel like it, like paella.”

Contemplating his legacy, Roux seems clearly pleased about how he has inspired entire generations of chefs. He and his brother established the Roux Scholarship in 1984 to help young chefs in Britain acquire experience in French restaurants.

“My biggest thing in life is to pass on the things that I’ve learned. With my brother, we’ve trained more than 800 chefs – in Australia, America, Germany, France and the UK,” Roux says. “But I’ve been very fortunate. I left school and started working at 14. I worked as a chef for the Rothschild (banking) family and learned about art, finance, culture and wine before opening my first restaurant. I found luck in life and I grabbed it. But in the end, to be humble is the best sign of success in life.”