India’s first World Heritage City – the largest metropolis in the state of Gujarat – has a long and fascinating history which you can glimpse in the built landscapes that have endured through time

The last time I visited Ahmedabad was a decade ago. It was a short, whirlwind tour of a sprawling city dotted with glittering skyscrapers and modern highways on the eastern bank of the Sabarmati River. Even then it had captivated me with its ancient step wells, its centuries-old Jain and Hindu temples with magnificent spires, and its palatial mansions. The delicious vegetarian fare – like fafda, a crispy snack made with chickpea flour, and dhokla, a spongy savoury fermented cake made of split yellow lentils – was just as unforgettable.

India’s western state of Gujarat is home to a staggering 42 Unesco heritage sites, and the 600-year-old Ahmedabad has the distinct honour of being the country’s first Unesco heritage city, a title bestowed in 2017.

I returned to Ahmedabad recently, this time determined to appreciate its old-world charms at a more leisurely pace. I signed up for a 2km walk with Urvashi Panchal, a freelance tour guide specialising in heritage and textile tours. Her passion for Ahmedabad’s cultural treasures and for preserving the city’s built heritage for future generations is evident and infectious. It makes me pay closer attention. She and her husband Nirav share over four decades of combined tour guiding experience, and have worked closely with the Unesco committee on Ahmedabad’s inscription as a heritage site. Fun fact: their daughter was born on April 18, World Heritage Day.

We start at the bustling, centuries-old Dabgarwad market, a cacophony of clanking utensils and musical instruments being sold. The row of shops leads to the 19th century Swaminarayan Temple in Kalupur, the first temple of the Swaminarayan Hindu sect to be ever built. The ornate carvings and abundance of stunning colours leave me speechless. We leave our footwear outside and step into a temple with intricately carved arches and pillars, featuring striking sculptures of dancing women, religious icons and deities, all chiselled in Burmese teak. It’s a stark contrast to the market outside: although it’s abuzz with families paying obeisance, the atmosphere is hushed, and filled with the sweet aroma of incense sticks and striking garlands of fresh marigolds.

Urvashi gives me a recap of Ahmedabad’s ancient history in bullet points: the city traces its origins to the historic Ashaval, once ruled by the Bhil tribe. Later, under the long reign of Chaulukya rulers that began in the sixth century, it flourished as Karnavati – a name you still hear today.

Ahmedabad as it is known today was founded by Ahmad Shah I of the Gujarat Sultanate in 1411, who built a wall – punctuated by 12 gates known as darwazas – around the city. Inside the old walled city, we stroll down charming lanes of Ahmedabad’s traditional residential clusters called pols.

Constructed during a period of heightened communal tensions and societal upheaval centuries ago, the pols – from the Sanskrit term Pratoli, meaning gate – comprise residential enclosures designed as mini-fortresses, featuring secret passages, narrow lanes and a shared, enclosed courtyard , ensuring security and privacy to its residents, typically people of similar caste, religion and occupation. The pols also feature havelis or palatial mansions, markets, temples, intricately-carved bird feeders known as chabutras, and community wells – hallmarks of self-sustaining gated communities.

“The Unesco heritage city tag has helped in attracting tourists to these residential communities like never before,” Urvashi tells me. True enough, there were a number of tourists gazing up at the havelis, taking photos and looking transfixed by the details: stone masonry structures adorned with intricate wooden facades, windows and doors, a sensory overload in the best way possible. Amidst them, Art Deco mansions evoked the city’s much recent colonial heritage.

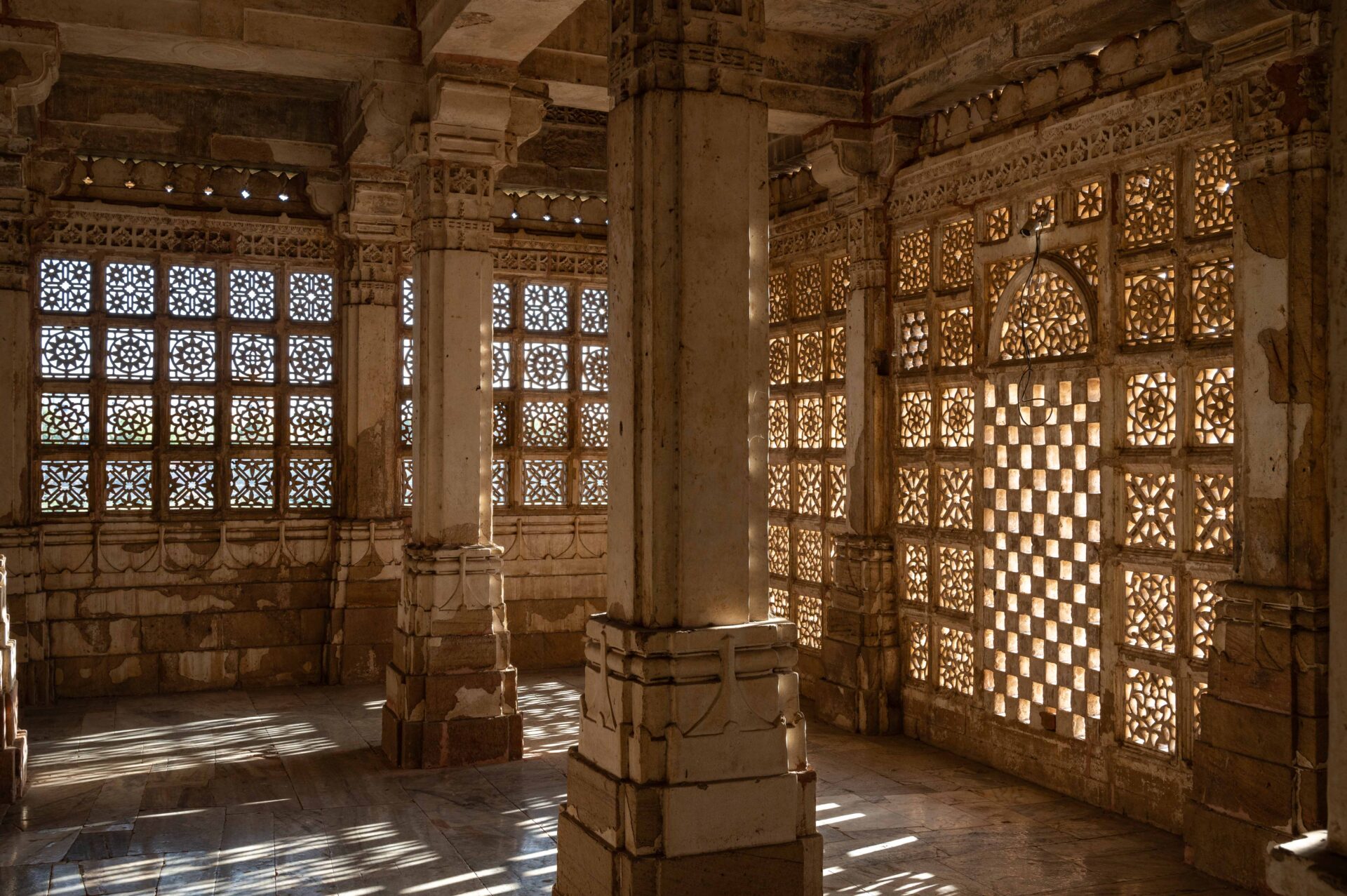

We walk through secret alleys connecting various pols – 600 pols across the six neighbourhoods within its walled city – past sandstone Jain temples with exquisite carvings and ending at the 15th-century Jama Masjid built in yellow sandstone. Its central courtyard houses an ablution tank for rituals, and is flanked by a prayer hall of 260 columns and 15 domes. The structures were formidable and impressive, but the more lasting impact of the trail was the understanding that Ahmedabad is an incredibly diverse city that’s embraced people of various faiths and religions, from Gujaratis to Jains, and Muslims to Hindus.

The next day, I make my way to another 15th-century structure, the Sarkhej Roza, located across the Sabarmati River in Makarba. Dedicated to Ahmed Shah’s spiritual mentor Shaikh Ganj Baksh Khattu, the complex has an expansive reservoir, mausoleums and pavilions. Both the Sarkhej Roza and the Sidi Saiyyed Mosque are fine examples of Indo-Saracenic architecture encouraged by the Sultanate.

Against this rich tableau of medieval architecture, more recent buildings championed by local contemporary philanthropists and global visionaries add texture to the city’s overall look and feel. The home of Mahatma Gandhi, iconic leader of India’s independence movement, at Sabarmati Ashram – built in 1915 on the banks of its eponymous river – was expanded over time with an interactive museum and library, by Indian architect and urban planner Charles Correa. Mr Correa is widely credited with defining the modern architectural style of post-independence India, and the home features vernacular elements like wooden doors, stone floors, an open courtyard, spacious functional rooms and a rather enthusiastic use of brick.

Nearby was a hut-like structure, where I tried my hand at the charkha – the spinning wheel popularised by Gandhi, which became a symbol of India’s defiance and resistance against British rule. Spinning the charkha was a meditative experience for me, evoking a profound sense of reverence for the thousands of freedom fighters who sacrificed their lives to liberate the country.

Following India’s independence in 1947, a wave of enthusiasm for development swept over prominent business clans who wholeheartedly invested in shaping the city’s architectural and cultural landscape, says historian Ishita Shah. It was a new era for the city, for the country and the powerful entrepreneurs who wanted to leave their mark.

The Calico Museum of Textile, founded in 1949 by Gira Sarabhai and her brother Gautam Sarabhai, is one such example. Another sibling, Vikram, is the founder of India’s space programme. Post-independence, the influential Sarabhai family, whose patriarch was a major industrialist, branched out to several fields, from real estate and pharmaceuticals, to textile manufacturing and the arts. Philathropy was a family affair. The museum stands out as Ahmedabad’s first modernist architectural space. Gira, an architect and designer as well as the museum’s curator, fused functionality with aesthetics in its design, symbolising the city’s dominance in the textile industry.

Emerging scions of prominent business clans, eager to make a stamp on the city, also began engaging renowned architects to shape modern landscapes. The works of Le Corbusier, the Swiss-French visionary, epitomised functionalism by using a modular grid system and climate-responsive architecture in layouts, and bold sculptural expressionism in projects like the Mill Owners’ Association and Sanskar Kendra City Museum. Le Corbusier was later commissioned to design the Sarabhai family villa.

Meanwhile, the Estonian-born Louis Kahn, among the greatest American architects of the 20th century, collaborated on the sprawling Indian Institute of Management (IIM) campus at the invitation of architect Balakrishna Doshi.

According to Ishita, Louis Kahn – hired by Vikram Sarabhai and Kastrubhai Lalbhai, another industralist and philanthropist – designed the campus buildings with expansive arches and circular openings, intertwining aspects of decolonisation and Indian culture.

Today, the latest addition to the city’s evolving architectural landscape is the 300m Atal pedestrian bridge that connects the eastern and western banks of the Sabarmati. The design is inspired by the city’s love for kites.

I spend an evening on the beautiful Sabarmati riverfront, where an urban regeneration and environmental improvement project has been unfolding since 2012. Before the makeover, the flow of the river had been hampered by encroachments and silt deposited over the years. The river had dried up, and the land was being used by circus companies and as a playground. Now the rejuvenated river, its manicured riverbank lawns and entertainment facilities are already a popular hangout among locals.

On the last day of my trip, I visit the 11th-century Rani ki Vav, a Unesco World Heritage Site. Commissioned by Queen Udayamati to honour her husband Bhimdev, the seven-storied Queen’s Stepwell resembles an inverted temple, beautifully embodying the Maru-Gurjara architectural elements of lavish sculptures, and functional spaces built in sandstone.

It’s one of Ahmedabad’s oldest built structures, and yet it remains one of its most visually arresting and photogenic. The cascading flight of stairs through multiple levels reveal intricately carved pillars, and over 800 sculptures depicting natural elements, geometric patterns and deities of the Hindu pantheon. The fourth level, the deepest, leads to a majestic rectangular reservoir of water plunging to 23m.

Urvashi tells me that these stepwells in and around Ahmedabad show how these ancient cultures placed importance on water management – a community effort – and that they had the foresight to prepare for hot and dry seasons. They’re a timely reminder, in this age of climate emergencies, of the architectural wisdom of its past rulers and architects and how the spirit of innovation can help meet the challenges of today.