For more than 2,000 years, Chinese landscapers have curated beautiful gardens infused with philosophical messages

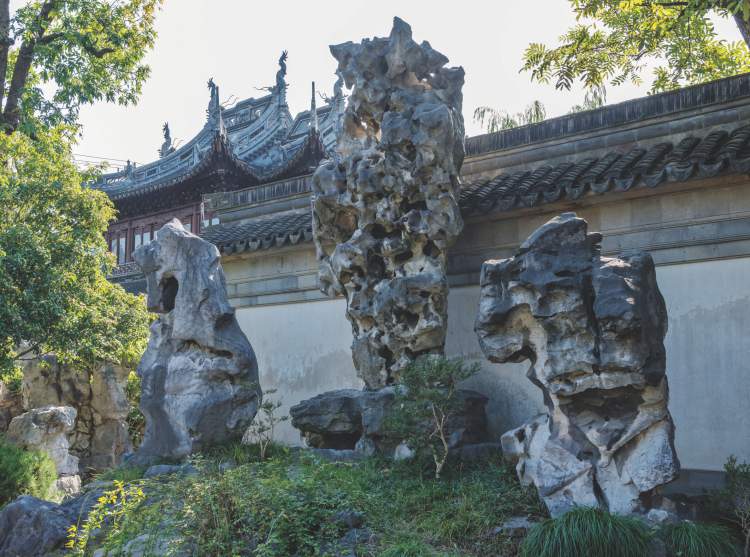

To the casual observer, it is just a rock. Porous and crumbling, the large slab of Taihu limestone has been ravaged by the elements. To the more refined gaze, it simultaneously signifies the past, present and future. Its foundation symbolises its original sturdiness, while its weathered exterior highlights the effects of time and hints at the decay still to come. These connotations are invisible to many people. But the concepts are all there, just waiting to be appreciated by those who can read one of the oldest and most complex languages of China.

Taihu rocks are a common feature of Chinese classical gardens, which feature complex layouts imbued with deep meaning. Each stone, pond, path, stream, pagoda, bridge, walkway and flower is meticulously positioned within these gardens in accordance with philosophies more than 2,000 years old. Together, they form a language that hides in plain sight. It is decipherable only by people who have a grasp of Taoist beliefs and how these ideas have shaped the design of Chinese classical gardens for millennia.

Key among these guiding philosophical principles is the concept of the Tao. In Taoism, one of China’s oldest and most influential belief systems, the Tao is all that has existed and will ever exist. It is the past, present and the future all at once. It is the state of flux, of constant evolution in which our world lives. Chinese classical gardens attempt to portray this simultaneous sense of beauty and fragility.

This may seem a needlessly complicated idea upon which to base the design of a garden. But in ancient China, classical gardens were not merely green spaces where people communed with nature. They were high art. They were expressions of intellect. They were symbols of religious dedication.

From the time of China’s Han Dynasty (206BC – 220AD), the design of classical gardens has been linked to landscape paintings. These art forms developed side by side, each drawing inspiration from the other. Traditional Chinese paintings focused heavily on nature, brimming with snow-draped mountains, crystalline rivers, verdant forests, lush plains and pristine lakes. The aim of the garden design is to recreate these same natural wonders in a limited space.

Historically, the difficulty of this task varies, depending on whether the garden designer is making an Imperial garden or a private garden. The former is typically located outside the city’s limits, spread across a large parcel of land and intended to merge with its natural environment. The latter, meanwhile, is confined to the grounds of a residence, intended to be small-scale recreations of the natural environment.

The most famous surviving Imperial gardens are in northern China – Beijing’s Summer Palace and the Chengde Mountain Resort. When I visited the Summer Palace, which was first built in 1750, I was struck by the way it carefully blends its natural features of hills and lakes with artificial constructions like halls, palaces, pavilions, temples and bridges. This achieves the Taoist aim of balancing the works of man with nature. There is similar harmony at the Imperial Xu Garden in Nanjing, a peaceful space dating back to the 1300s.

Another ancient Chinese philosophy is evident at Chengde Mountain Resort, a sprawling complex of Imperial palaces, temples and gardens spread through forested hills 150 kilometres northeast of Beijing. Built in the 1700s, the gardens at Chengde were constructed using the principles of feng shui. This Chinese belief system aims to organise interior and exterior spaces, so humans are in harmony with their environment.

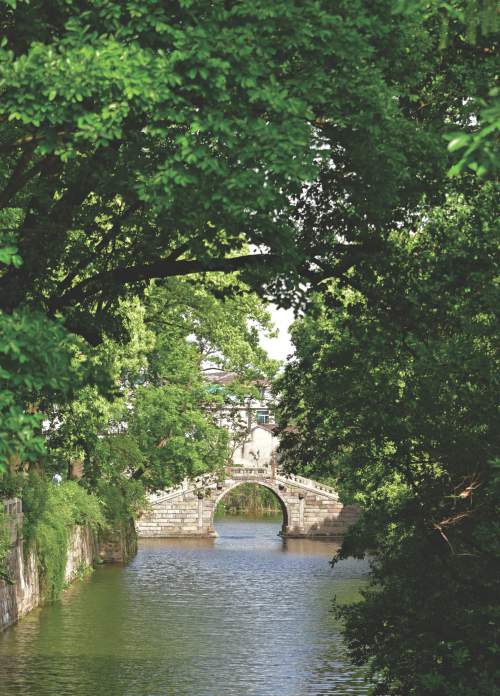

Feng shui, which has been used in Chinese architectural and garden designs for more than 1,000 years, dictates that a space should be constructed with a natural flow, so humans can move through it instinctively and with ease. This is evident throughout China’s classical gardens, including those at Chengde. Paths and walkways guide visitors through the gardens, transporting them from tighter spaces out into open areas, from higher to lower ground, revealing views and concealing them soon after.

As with all classical gardens, visitors should not be able to see all its features at once. Instead, exploring these gardens is meant to be a journey. New experiences and sights emerge as one delves deeper into these spaces. This concept of garden layout is inspired, in part, by scroll painting, which was invented in the eighth century by renowned Chinese artist and poet Wang Wei. These paintings are slowly unwound from left to right, revealing each scene in sequence and allowing the artist to control what the viewers see and when they see it.

This strategy of concealing and revealing became central to the layout of private gardens since then. Because these gardens must be attached to homes, they often had to be squeezed into small plots of land. Within these boundaries, artists tried to create microcosms of nature. Mounds symbolised hills. Rocks signified mountains. Ponds represented lakes. Streams acted as rivers. Groves stood in for forests.

In this way, the gardens boasted two spirits. One form of energy came from its natural attributes and the other from the artistic choices of its creator. Visitors to these gardens are not just interacting with nature but also with the symbols and meanings embedded into the space by its designer. Having an especially intricate private garden is seen as auspicious, and aristocrats would compete to have the most impressive outdoor space at their homes.

Many of these ancient private gardens no longer exist, although fine examples remain in Suzhou and Shanghai. Yu Garden in Shanghai was built in 1559 for a public official and is now one of the city’s top tourist attractions, thanks to its labyrinthine layout of graceful pavilions, zig-zag walkways and fish-filled ponds.

It is Suzhou, though, which still boasts more of these gardens than any Chinese city. This art form flourished here between the 16th and 18th centuries when there were up to 200 private gardens in Suzhou as wealthy locals used them as status symbols. Known as China’s hub of classical gardens, Suzhou boasts more than 60 historical green spaces that are still intact.

I slowly climbed to the crest of the oldest of Suzhou’s gardens, Tiger Hill, which dates back almost 2,500 years. As I stood under the towering Yunyan Temple pagoda, I looked down at this enormous Imperial-style classical garden, with its sequence of carefully arranged groves, ponds, streams, paths and pagodas.

Even more impressive is the nearby Master of the Nets Garden. I marvelled at the way the designer of this private garden, built in the 12th century for an Imperial minister, managed to create a sense of immense space within an area of just 5,000 square metres. The similarly spectacular Lingering Garden and Humble Administrator’s Garden in Suzhou are two and five times that size, respectively.

The philosophical concepts behind these gardens are not entirely hidden. Throughout many of these spaces are signs emblazoned with calligraphy of Taoist or Confucian quotes, which often cryptically hint at the meaning of that section of the garden. This is one of the great contrasts of these spaces. They were designed both for intellectual stimulation – for the pondering of Taoist philosophy – and for switching off mentally and entering a state of meditative bliss.

Useful tips to know

- English is not widely spoken in China, so tourists should arrive prepared with Mandarin phrase books or with one of the many Chinese travel apps designed to make your holiday easier.

- Having a local SIM card is crucial when travelling in China. The easiest place to buy one and have it set up is at the airport, so get it upon arrival.

- Known as the ‘Venice of the East’, Suzhou’s Old Town area is pierced by a sequence of canals. Set aside time to wander along these canals and soak up the ambience.

- Thanks to China’s fantastic bullet train system, Shanghai, Suzhou and Nanjing are all easily accessible. Use Suzhou as your base to explore the classical gardens of all three cities.