Hanji proves its worth in tradition and modern culture

“Koreans have been using hanji in daily life for a long time – we used to say that hanji is with us from birth to death.” These are the words that Hyeon-a Im, who works in the department of research and development at the Hanji Industry Support Center (HISC) in Jeonju, North Jeolla Province, uses to describe the prominence of hanji, or traditional Korean paper, made from mulberry tree fibre.

The HISC is the perfect place to discover the history of this important element of traditional Korean culture, as well as get a peek at the future that lies ahead for hanji. The first two floors of the two-year-old centre are for visitors to explore the museum or have a more hands-on experience constructing hanji crafts or even making sheets of hanji to take home. The top two floors are for research and development, where the staff of 10 searches for new techniques and uses of hanji.

Jeonju is a fitting home for the HISC, as it is one of three representative centres of hanji production in Korea, along with Wonju and Andong as well as drawing visitors from all over the peninsula and abroad to visit its hank maul, a preserved traditional folk village. Im credits the fine quality of Jeonju hanji to both the high quality mulberry grown by local farmers, and the quality of the water used for hanji production from Joenjucheon Stream, with its near-neutral acidity.

No records or relics exist that tell exactly when paper was introduced to Korea. However, multiple sources claim that Koreans had already developed paper-making skills by the early part of the Three Kingdoms Period (57 B.C. to 668 A.D.). Government regulation throughout history helped ensure paper quality and oversee supply and demand of raw materials for paper-making. However, despite a reorganisation of government-run paper-making in 1882, a fatal blow for keeping alive the tradition of high quality hanji-making came shortly after with the arrival of Western paper machines from Japan. For much of the 20th century, changes in lifestyle and the importation of cheap paper gradually decreased the demand for traditional hanji. Recently there has been more and more renewed interest.

Part of this revival stems from the efforts of organisations such as the HISC. Though hanji has traditionally been used for various household and artistic purposes, it has begun to transcend its traditional function, developing into a modern industrial material, attracting attention for its functional versatility and friendliness to the environment. Hanji products are being used for window coverings, wallpaper, flooring paper, curtains and even carpets. Furniture covers, photographic paper, bankcards and IDs, and even speakers – all made of hanji – are on display at the HISC. Innovations such as these will help ensure that this material will continue to be a functional part of daily life.

However, for some Koreans, such as Lee Misun, a resident of Gwangju, South Jeolla Province, hanji serves not just as a functional part of the modern world but also as a link to a bygone way of life, specifically through traditional hanji craft-making. An unplanned visit to a hanji craft shop five years ago helped shaped her course going forward via this material from Korea’s past. “The moment I felt the texture of hanji, I decided my future,” explains Lee, now the owner of the Habaek hanji craft shop in the Juwol neighbourhood of Gwangju.

Prior to participating in an introduction program during that chance visit, Lee knew nothing about hanji. At the time she was working as a nurse. “I was under a lot stress, but just the touch of hanji relieved my stress, and while making hanji crafts, I felt a warm and soft feeling embrace me and it was then that I decided to pursue hanji craft-making as a job.”

After completing a professional course during her days off, Lee opened her shop in November 2012. There, her own work is on display, both for sale and to provide examples for the students she instructs to choose what project they want to attempt.

Most students start by making a hanji lamp as their first project. Hanji lamp-making is one of Lee’s specialisations and provides her with a connection to her faith, as the lamps remind her of candles used in Christian worship. “When the lamp is on, I can feel God’s presence in its glow,” she explains. The hanji comes from Jeonju and students can choose to attempt projects as diverse as the aforementioned lamps, to boxes, drawers, decorative clocks, to even medium-sized tables.

Lee states that most of her customers are women, usually in their 30s and 40s, ranging from housewives, to teachers, doctors or nurses. The atmosphere of the little shop could be described by the Korean idea of sarangbang, or what might be called a ‘sewing circle’ in English. There is a small set of regular customers, to which less frequent visits and newcomers alike are warmly welcomed, who gather to learn and work on a craft that will adorn their home or perhaps serve as a gift with a personal touch. Knowledge of hanji, however, is not all that is shared, but also a sense of community, a tradition in Korea as timeless as the material that is the focus of their efforts. Lee’s greatest sense of enjoyment, however, comes from teaching knowledge of this traditional craft “to spread the feeling of hanji”.

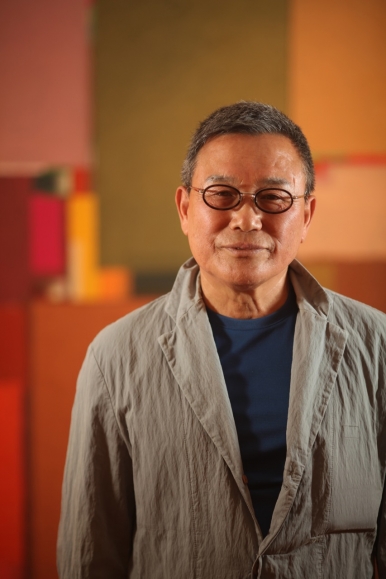

Though it was the texture, or “feel,” of hanji that attracted Lee, it was the vibrant colours that drew prominent Gwangju artist Woo Jae Gil to incorporate traditional Korean paper into his artwork. “While visiting a gallery in Seoul that specialised in hanji, I was attracted to its colour. It was touched by hang’s pure colour and texture and I made up my mind to work with hanji.” Though woo first started to work with hanji more than two decades ago, it was after this recent rekindling that he began to arrange hanji sheets of different colours onto panels to form collages that represent farm fields in the southern part of Korea. The artist explains the use of hanji to represent nature: “The colour of hanji is more natural than other colours, so it gives a feeling of softness.”

Woo attributes that quality to the traditional manufacturing technique: “Hanji is manufactured differently from Western paper. Western paper is made from materials turned into powder and pressed. But hanji first blends the pounded inner bark of mulberry in water, which is then scooped out with a bamboo sieve to be dried in the sunshine. That is why every natural texture is alive there. It is nature itself.” He elaborates on the allure of using a product produced in a traditional fashion, saying, “even though I am a modern artist I like the materials of the past.”

Woo is not sure how long his recent surge in output featuring hanji will continue, but he admits “Several years have passed by, but I am fascinated working with hanji so I can work several months in a row without becoming bored.” Even if his passion for working with this traditional Korean material ends tomorrow, the works he has already created, as well as the products being developed at the HISC in Jeonju and the crafts and community being fashioned at the Habaek craft shop, will all serve as a testament to the vibrant, living nature of hanji in Korea well into the future.