Beyond a creative pursuit, the art of pandanus weaving holds significant economic and cultural value among Malaysia’s indigenous people

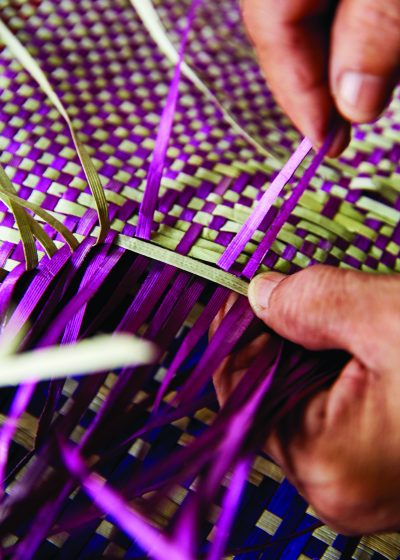

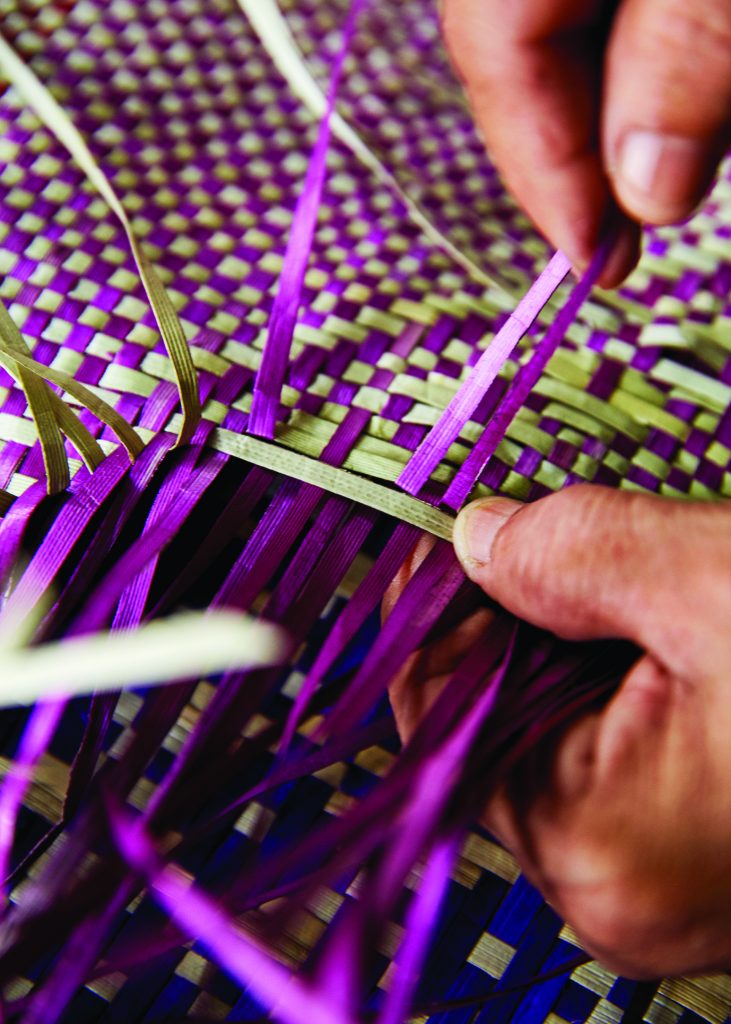

We cross a bridge, traverse a brook and ascend a flight of cement stairs before we reach our destination: a rustic, single-storey, wooden-and-cement dwelling enshrouded in banana stems, papaya trees and other jungle plants.Inside, a bespectacled lady in a baju kurung (traditional Malay dress) sits cross-legged on the floor. Her fingers, marked by age, deftly weave strips of colourful pandanus leaves, as if she were braiding her daughter’s hair. On the table and wall behind her, an array of pouches, bags, baskets and fishing traps is on display. This is where 65-year-old Abok a/p Angah spends her time practising the traditional craft that is the pride of her community.

Originally from Kampung Tenrek in the northern Malaysian state of Kelantan, Abok belongs to the Temiar, the second-largest of 18 indigenous Orang Asli sub-groups in Peninsular Malaysia. Predominantly concentrated in the jungles of southwestern Kelantan and northern Perak, the Temiars are known for their formidable forestry knowledge. Temiar women are celebrated for their skills in producing beautiful utilitarian and ceremonial crafts out of screwpine (pandanus).

Both Abok’s mother and grandmother were active weavers. “They never taught me formally. Nor was I particularly interested. As a child, I only wanted to play with my friends,” she confesses laughingly. Despite her indifference at the time, the constant exposure to weaving helped Abok internalise the skill, which turned out to be a lifesaver eventually.

The 1970s and 1980s saw the development of a thriving Orang Asli settlement in the district of Gombak, and Abok moved there to join her husband, who worked as a medical attendant. Following the birth of their third child, Abok longed to contribute to the family income. She remembered how her mother would sell woven pandanus products for RM20-RM30 (USD4-USD7). “Not a fortune, but enough to purchase salt, sugar and tea for the family. I decided to follow her footsteps and pick up weaving again.”

Abok’s pragmatism is very much in keeping with the role of women among Orang Asli. “We are really an egalitarian society,” explains Raman bah Tuin, a fortysomething Orang Asli of Semai descent and family friend of Abok. “In a marital union, men and woman see each other as partners and both are expected to contribute specific skillsets. An eligible man is one who has hunting and building skills, while a woman should be good at weaving, cooking and looking after children.”

At the Gombak settlement, there are at least 20 skilled women weavers, but none of them are full-time. Pandanus weaving is laborious work, and with the advent of urban development, raw material is in short supply. Most of the weavers are getting on in age, and some, like Abok, have ailing health. It doesn’t help that the younger generation prefers to pursue other opportunities over learning a centuries-old craft.

In 2010, Raman co-founded Jungle School, a training programme that lets visitors experience an authentic Orang Asli lifestyle in an easily accessible location at Gombak. Participants get to go on jungle treks, build shelters from bertam leaves, and learn how to weave from skilled practitioners. Raman hopes to achieve two outcomes: one, the Orang Asli participants will gain an alternative stream of income, and two, outside interest will instill cultural pride in their heritage.

Amid our conversation, Abok shows us an intricate latticework mat. “This is the pattern my mother used to weave. It’s finer and more complex. My health is not so good these days, but when I look at it and think of my late mother, I somehow find the energy to do the work. ”

Raman says, “When cultural pride is strong enough, you will find the will to continue something and preserve it for generations to come.”