More than a century of pewtering makes Royal Selangor a Malaysian brand icon and one deserving of its royal warrant

The story of how one of the earliest creations – a melon-shaped teapot – of Royal Selangor founder Yong Koon made its way back to his descendants is often retold. Yet, it bears repeating because it is an incredible story of fate, one that has allowed the family to recover a piece of its past.

The story began in 1941 during the Second World War in the small village of Kajang, south of Kuala Lumpur. Bombs were falling and there was terror in the faces of the people on the ground. Among them was a man named Ah Ham, who, despite the shelling, was foraging for food to feed his family. As he ran into a warehouse to grab some bags of rice, he spotted instead a shiny glimmer partly hidden in mud. As he bent down to pick up the object, shrapnel flew over his head. The object turned out to be a melon-shaped teapot. For the next 30 years, whenever friends visited, Ah Ham would serve tea from the teapot and repeat the tale of how it had saved his life.

The story soon reached the ears of one Chen Shoo Sang, whose wife, Yong Mun Kuen, is the granddaughter of Yong Koon. Shoo Sang decided to visit Ah Ham, who upon learning that he owned a pewter factory, asked for the teapot to be cleaned and polished. At the factory, workers cleaning the teapot discovered an etching at the bottom of the piece and determined that it was the hallmark inscription of Yong Koon. Elated by the discovery, the Yong family pleaded with Ah Ham to sell them the teapot. He refused. Years later, in his old age, Ah Ham changed his mind and decided that the teapot should return to its rightful owners. The precious teapot is now displayed in all its glory at the Royal Selangor Visitor Centre.

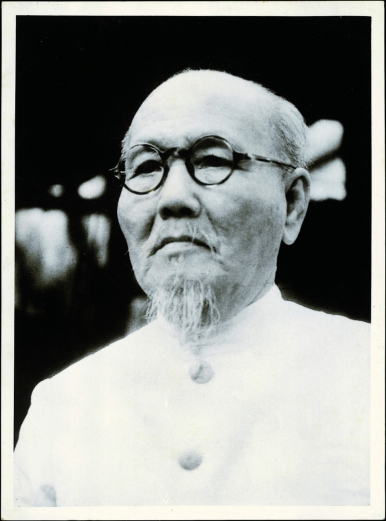

The story of how Royal Selangor became the world’s largest pewter maker is much like that of the return of the melon teapot to the Yong family – a saga, which began when Yong Koon, a young pewtersmith, sailed to then-Malaya from Shantou in Guangdong Province in 1885 in search of a better life. Already a skilled pewtersmith at the remarkable age of 11, Yong Koon came to Kuala Lumpur to join his brothers who were tinsmiths. Together, they made everyday items like pails and weighing scales, and Chinese ceremonial objects such as incense burners and candleholders. In 1930, Yong Koon parted ways with his brothers and began Malayan Pewter Works with his wife and their four sons. Business was tough with the company operating under severe economic conditions and the Second World War, and the four sons would eventually go their separate ways after a bitter feud.

By 1950, Yong Koon’s third son, Peng Kai, was the only one still in the pewter trade. He worked hard, roping in his wife and four children – two boys and two girls – who took telephone orders, packed pewter and painted labels on boxes. They sold pewter vases, pitchers, ashtrays, and cigarette boxes from a rented half-shop. Peng Kai moved the business into a new 370-square-metre factory in the Kuala Lumpur suburb of Setapak in 1962; by then, the business was known as Selangor Pewter. The name was changed to Royal Selangor in 1992 to reflect the company’s status as royal pewterer, as conferred by the Sultan of Selangor in 1979.

Now, 130 years after Yong Koon first arrived in Kuala Lumpur, Royal Selangor is the maker of arguably the most sought-after souvenirs and gifts for visitors to Malaysia. The company, now run by the third- and fourth-generation descendants of Yong Koon, offers more than a thousand different tableware and gift items, from contemporary homeware to traditional tankards, and personal accessories. All four of Peng Kai’s children are active board directors. The youngest, Poh Kon, has led the business since 1968. While he is still the managing director of the company, the daily running of the business has mostly been left to his son, Yong Yoon Li, and nephew, Chen Tien Yue. Tien Yue is the only son of Shoo Sang, the man who heard about the melon teapot and met with Ah Ham.

To meet international demand for new designs, Royal Selangor launches 10 to 15 new collections each year. Yoon Li discussed the company: “We have to look at the brand and the company holistically, whether we want to just make pewter products or add other materials to pewter as we’ve been doing for the past 20 years. It could either be objects of art or functional items. I think there is still room to continue pushing that space.”

Last year, in collaboration with a 300-year-old Japanese lacquerware brand, Zohiko, Royal Selangor launched one of its boldest pieces yet – the sculpture of a carp to symbolise human perseverance. The piece, crafted in pewter and then lacquered, relates the legend of a carp that swims against a surging waterfall and, as it makes its final leap at the top, transforms into a dragon.

In the words of Yoon Li, the story of Shori, or the ascending carp, has many layers and angles. “We’ve only told one part of the story. What happens after he goes over the waterfall? How does he look? Does he look victorious? And then when he becomes a dragon, what happens? This collaboration with Zohiko is a start. We still have much to learn. The way they treasure their craftsmanship, while keeping their heritage and history close to their heart is quite amazing. As Malaysians, we need to be proud of our roots too.”

Royal Selangor’s partnership with Zohiko isn’t its first collaboration. The company had for years worked with various designers and institutions such as Erik Magnussen of Denmark, Freeman Lau of Hong Kong, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. In 2011, the company teamed up with the National Palace Museum of Taipei to create The Imperial Collection. Some of the designs from these joint efforts have yielded international recognition.

He adds, “in this business, it’s quite a paradox, especially now, when technology is so available to you, the manufacturing of cars and even saucepans is all done by machines. If you speak to the guy on the street, he will say, ‘I wish that some things were still made by hand.’ But when you ask them, ‘would you like to make shoes?’ they’d say no. A lot of our customers love our products because they are painstakingly made by hand, finished by hand, and packed by hand.”

Royal Selangor’s factory in Setapak employs more than 250 craftspeople, and most are treated like family. Some have been with the company for years, starting out as apprentices and leaving only upon retirement. To ensure that the heritage and tradition is kept alive, the company established a training centre five years ago that allowed school leavers to learn the skills of the trade. Not all graduate. For every 10 students, eight drop out before completing their training. “At least there’s two!” quips Yoon Li. “Hopefully in the years to come, we’ll have a fresh batch of craftsmen and women. Whether they’ll stay for 30 years like some of them now, or 15 years, who’s to tell? But I’m hopeful. At the end of the day, it’s a very rewarding job to see something come alive. I think it’s a very basic human need to create something beautiful,” he says.