A third-generation sweet maker does his best to preserve the traditional ting ting candy

Using a hammer and chisel, Ah Chun chips methodically at a tray of looping white coils that resemble white marble before offering me one of the broken pieces. At first bite, the texture is brittle, even hard, but in seconds, the contact with saliva melts the candy into a pool of sugary sweetness. Suddenly, I am ten years old again, waiting at the gate for the arrival of the ting ting candy man.

Currently helmed by Chia Chun Chun – or Ah Chun for short – Jia Zhong Jia Food Enterprise is one of the country’s few remaining makers of this traditional Chinese candy. So named because of the sound it makes the way it was originally sold, ting ting candy was transported by mobile vendors on bicycles who would break the hard candy with a hammer and chisel, producing a distinctive metallic sound to announce their arrival. Chia Song – Ah Chun’s late grandfather and the founder of the business – was one such “ting ting man”.

Once a fixture in neighbourhoods and cities, the ting ting man is a disappearing breed in Malaysia. With the surge in health concerns and competition from other sweet products in the market, the family has had to adapt to survive. When Ah Chun’s father took over the business, he traded the bicycle for the motorbike, and eventually, supermarkets and retail outlets became their main points of sale. Today, helped by his sisters and mother, Ah Chun primarily supplies to mobile traders in night markets because “cash transactions mean no bad debts”. Custom orders through Facebook are also becoming popular.

While the family has had to evolve the business model, the candy’s recipe is unchanged: a secret formula of maltose and honey, as opposed to popular versions that involve maple syrup, sugar and glutinous rice. Sesame seeds are added for extra crunch and aroma. They have also come up with funkier flavours like peppermint and ginger to cater to modern taste buds. The sweets can last up to six months if kept away from sunlight even without refrigeration.

Involving only three main steps, the candy can be made even in a home kitchen, but the process requires considerable kungfu (skill). It starts easy –cook the honey and maltose together at a temperature of 100 degrees Celsius until it achieves a honey-golden colour. Then the mixture is placed over a pot of water to cool. As it loses heat, the mixture congeals into a translucent honey-golden dough.

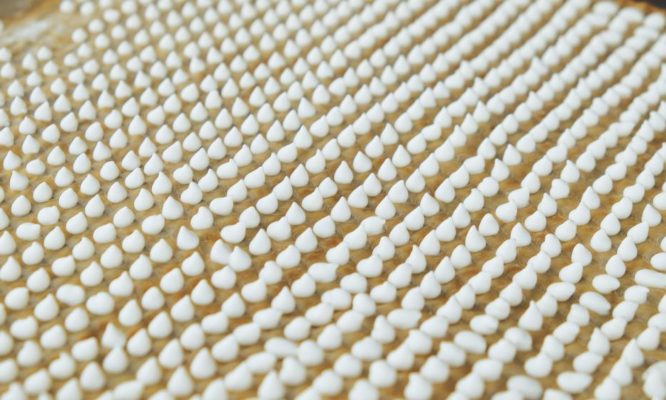

The next step is the trickiest. Using a Y-shaped stick on the wall as an anchor, loop the dough over it, then pull and stretch repeatedly – imagine making ramen noodles – until it changes shape and colour into milky-white ropes that form the foundation of the ting ting candy.

The metamorphosis is quite a sight to behold; at one point, the sesame seeds sparkle through the translucent strands of dough like gold dust. I’m not surprised when Ah Chun confesses, “As a young teenager, I helped my father pack the candy at home. They looked so delectable that I couldn’t resist popping a few into my mouth when his back was turned. That is why some of my front teeth are missing!”

Now 28, Ah Chun pursued accountancy studies but ultimately he couldn’t let the family business go without a fight. He shows me the 70-year-old hammer and chisel that his grandfather brought all the way from China. These days, the toolset is only brought out of retirement when Ah Chun sets up stall at food fairs during major Chinese festivals.

“This set of tools is a beloved family treasure,” he says nostalgically. “My forefathers have been able to raise their families by selling ting ting candy. We, as the next generation, have a responsibility to do our best to carry this tradition into the new era.”