This Eid, enjoy lemang, a beloved festive staple, with a twist

Pull it downwards, I’d been instructed, as if you’re peeling an onion.

Cradling the purple-skinned vessel in my palm, I grip the tiny flap of skin at the rim and start pulling. Lo and behold, the skin unravels to reveal a mound of glistening glutinous rice, warm and yielding to the touch. Inhaling the aroma of coconut milk infused into the grains, I take a tentative bite out of my very first lemang periuk kera (lemang in pitcher plant).

Using pitcher plants instead of bamboo stems as casings for lemang, a traditional Eid staple food enjoyed with sweet-spicy serunding or rendang, may sound like a novelty. But in some jungle-rich states of Malaysia such as Pahang, Johor and Sarawak, this method of preparation has been practised for centuries. For the last 15 years or so, residents in the Klang Valley have been fortunate to savour this unique delicacy, thanks to a resettled Pahang native who makes it to order.

Tall, buff and strapping, Noorshafry Abdul Malik– who looks closer to soldier than chef extraordinaire – comes from a family of cooks: Grandpa was a kenduri king, his mum was a nasi lemak vendor, while his dad would sell lemang during festive occasions like Eid. An avid nature-lover, he enjoyed the occasional trek into Endau Rompin National Park, which was a stone’s throw from his village. During one such expedition, a military doctor shared how he ate wild rice cooked in pitcher plants in Borneo.

Intrigued by the idea, Atan, as he prefers to be called, decided to experiment with cooking lemang in pitcher plants, since they grew in abundance at his hometown. He achieved a satisfactory formula after three months, which he put to the test when he moved to Selangor state to start a catering business. In 2010, he was invited to take part in a 1001 Unique Foods Of Malaysia exhibition. The dish even garnered a mention on popular local children’s animated program Upin & Ipin in 2013.

The ingredients for lemang periuk kera are fairly standard – glutinous rice and good coconut milk, freshly squeezed. The real challenge is the procurement and preparation of the pitcher plant. Unlike bamboo stems that can be easily bought in markets, pitcher plants have to be manually collected from the jungle.

Each collection trip can easily take half a day, so Atan only accepts a minimum order of 10 kilogrammes on non-festival days. While there are over 100 wild species of pitcher plants in Malaysia, only Nepenthes Ampullaria – which has been certified safe for consumption by the Health Ministry – is used for lemang. The plant flourishes in swampy forests and cool areas around lakes. Once they’re collected, the plants must be used up in 4-5 days before they start wilting and blackening.

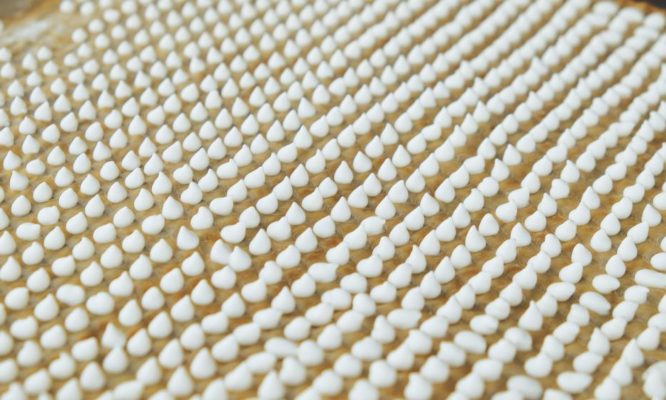

Before they can be used, the pitchers have to be rinsed with clean running water several times. Atan also snips off the lid, bristles and the tendrils that link the cups with the plant’s leaves. Once they’re thoroughly cleaned, the cups are filled with raw glutinous rice. As a final step, Atan injects each pitcher of rice individually with santan so that he can control the amount, before arranging them in a steamer to be cooked. He is so fastidious about taste that he uses mineral water for steaming because regular tap water has chlorine, which affects the taste.

I notice that the skin of the pitcher has thinned considerably after cooking. Atan explains, “During the cooking process, the nutrients from the pitcher cup will seep into the rice, making it even tastier and aromatic than your garden-variety lemang.”

Scientific theory or salesman talk? I’ve no idea. But having finally eaten the lemang periuk kera I’ve heard so much about, I must agree on the taste: soft, decadently creamy and incredibly aromatic, it’s good enough to eat on its own.

Note: Best enjoyed within three days if stored at room temperature. Do not keep in lidded containers as the coconut milk will turn rancid.