Malaysian screen legend Tan Sri P. Ramlee would have been 90 this year had he survived a heart attack at the age of 44. His death on 29 May 1973 rippled through the nation, causing a collective sense of guilt that in the years before his death, Ramlee’s work had been discredited and regarded as irrelevant. A jack-of-all-trades, he was an actor, director, singer, composer and producer whose name was recognised beyond Southeast Asia, even in Hong Kong and Japan.

Born Teuku Zakaria on 22 March 1929 to Aceh native Teuku Nyak Puteh bin Teuku Karim and Penangite Che Mah Hussein, Ramlee received his early education at the Kampung Jawa Malay School, the Francis Light English School and the Penang Free School. Although he had been described as a “reluctant student”, Ramlee was also known to be gifted in football and music.

While at the Penang Free School, Ramlee’s education was disrupted by the Japanese occupation of Malaya from 1942 to 1945. He was forced to enrol in the Japanese navy school in order to continue his studies, but it was here that he received his foundation in music. He even learned to sing in Japanese. After the war came to an end, he continued to hone his musical skills and advanced his knowledge with private lessons. Ramlee’s career in acting began when he moved south to Singapore to join a studio that was expanding into the Malay and Cantonese market.

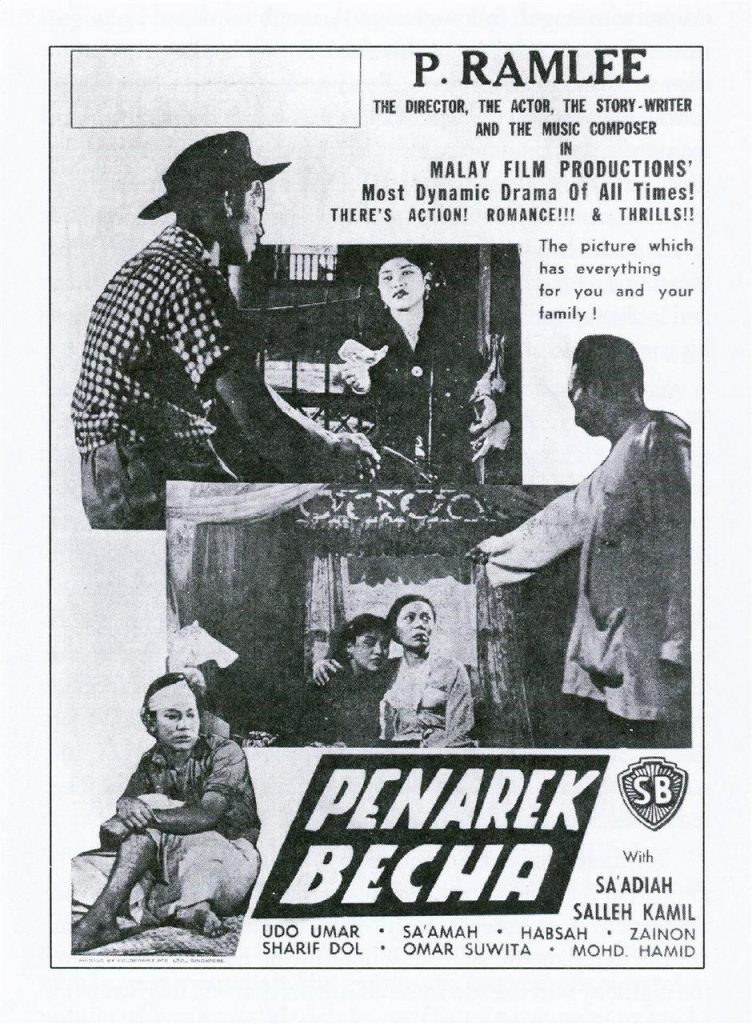

Shanghai film magnates Run Run and Runme Shaw had built a studio on Jalan Ampas in 1941, providing up-to-date technology and hiring top talent to work on films. In 1948, under the Shaw brothers’ newly incorporated company called Malay Film Productions, Ramlee starred in Chinta. B.S. Rajhans, an established director from India, directed his debut screen role.

In the following years, his career soared in almost 30 Malay-language movies, all backed by the Shaw brothers. One of his better-known films was Nujum Pak Belalang (The Fortune Telling of Mr. Belalang), a comedy released in 1959. Adapted loosely from a Malay folk story, the movie follows the hilarious exploits of an ordinary man who pretends to be psychic to help a sultan and his subjects.

By the mid-1960s, Ramlee’s appeal seemed to have diminished. Various factors may have contributed to the decline in Ramlee’s marketability. In a post-independent Singapore, newly separated from Malaysia, labour unions formed, causing frequent disruptions in the film industry. He also faced hefty competition from Hong Kong films, which were garnering top sales at the box office, even in Malaysia. Ramlee moved to Kuala Lumpur, where he turned to directing films for a production house called Merdeka Studios, also run by the Shaw brothers. But a fledgling film industry in Malaysia was not conducive to reviving his stardom – the lack of quality actors and reduced budgets prevented Ramlee from producing movies like before.

Ramlee passed away in 1973 after suffering a massive heart attack. Before his death, he was rumoured to have been so destitute that rice and fried eggs were all he could afford, and his widow, fellow actress and singer, Saloma was unable to pay for his funeral. Friends dispute this, saying he had been well-paid for every movie he made and even lived in a house that was paid for by the Shaw brothers.

In an interview with Malay daily Utusan Malaysia, close friend and musician Datuk Dr. Ahmad Nawab explained: “He was paid RM25,000 for every film he made, and during the ‘60s, that was not a small amount.” Ramlee was one of the few individuals who also received a monthly salary from the Shaw brothers, and his wife Saloma was employed as a singer, so he added.“Surely their financial situation was not sobad? I’ve heard rumours of P. Ramlee being so poor that he could only afford to eat eggs, but I absolutely don’t believe it.”

Regardless of his true financial situation, Ramlee was widely known to have been generous in helping out friends who needed money. Anyone who came to Ramlee’s home seeking financial support was rarely turned away, especially those who needed fare money to return to his home state of Penang.

Today, Ramlee’s reputation as a gifted artist is intact. Multiple buildings and a street in Kuala Lumpur have been named after him, and he has received several posthumous titles from Malaysian royalty.

In Penang, fans can visit the P. Ramlee House, a museum that houses his personal memorabilia and honours the family history – the house is a traditional Malay kampung design, built by Ramlee’s father. In his entire career, Ramlee was said to have contributed to more than 60 films. Ramlee also composed nearly 250 songs, including Getaran Jiwa, a beloved Malay classic often covered by modern artists. Ramlee left behind a creative legacy, now preserved as a national treasure for new generations to discover.

*This article was first published in Going Places Magazine in July 2017.