The Lost Food Project to the rescue.

Words Tan Lee Kuen Photography SooPhye

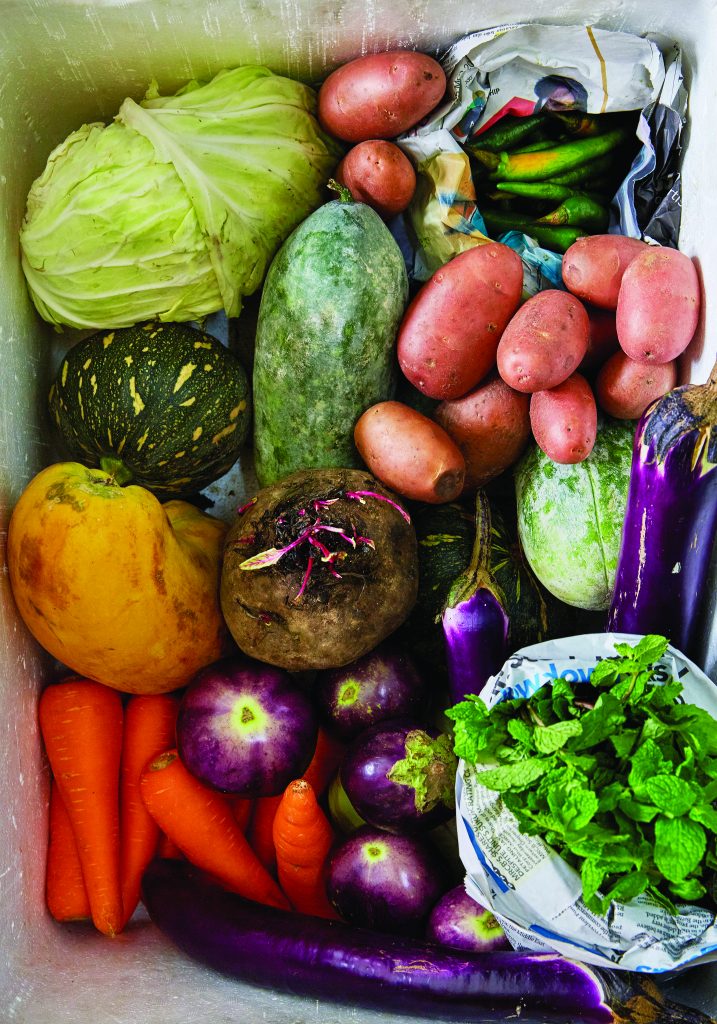

In a small warehouse in Kuala Lumpur, volunteers are sorting through boxes of produce and dry food such as eggplants, potatoes, lettuce, tomatoes and noodles. The produce is arranged into piles (with the obvious inedible ones put aside to be composted) and divided into portions that will then be delivered or picked up by various charities.

This is just a typical morning at The Lost Food Project. Founded in 2016 by British expatriate Suzanne Mooney, together with a group of parents from her children’s school, the non-profit organisation works with supermarkets, manufacturers and markets to pick up their surplus food and distribute them to charities around town. To-date, The Lost Food Project has rescued more than 500,000 kilograms of surplus food from its donors and provided almost two million meals to those in need.

“Our core function is as a food bank. Our driving force is to feed people, but the knock-on effects are to do with the environment and sustainability,” says Mooney, who often cites Robert Egger, the founder of DC Central Kitchen in the U.S., as an inspiration for setting up the NGO.

According to the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation, 1.3 billion tonnes of food are wasted every year, whether through production or consumption. That is a third of all food produced, a staggering amount that can feed up to 45 percent of the world’s population.

In Malaysia, where food is an obsession and not just a necessity, we are also guilty of wasting food, throwing away 3,000 tonnes of edible food every single day. That’s a lot of perfectly good meals being dumped in the landfill.

Food wastage is often described as a ‘farm-to-fork’ problem. Produce loss happens all along the food production chain, from the fields to transportation, factories, supermarkets, restaurants, and our fridges. Growing food requires water, arable land, energy, labour and money. Letting food go to waste is to squander these valuable resources while filling up landfills, which emit methane.

There are many reasons why food goes to waste. Part of it has to do with us, the consumer, and our expectations of food. For example, the demand for perfect and beautiful food means much of it is discarded. “If we see a fruit with a bruise or a dent on it, we would not take that and choose another one. Straightaway, we have created waste because we want perfection,” says Mooney.

When The Lost Food Project was first launched, a handful of volunteers were carting away a few boxes of groceries from Jason’s Food Hall direct to the charities. Today, they collect food from almost all the major supermarkets in town, including Cold Storage, Giant and Village Grocer. Standard operating procedures are in place and TLFP has contracts with its food partners to ensure due diligence.

One of their biggest accomplishments is working with Kuala Lumpur City Hall (DBKL) and the traders at the Selayang Wholesale Market, where they can pick up unsold fresh fruits and vegetables.

“It is very important to us that we give people a nutritious diet as well as feed them. We are about sustainability, but we are also concerned about society and don’t want to create more problems like obesity. We want to make people’s lives better,” says Mooney.

Every day, except Sundays, The Lost Food Project sends refrigerated trucks to pick up food from its food donors and bring it back to its warehouse, where the food is sorted by volunteers. Volunteers form the bulk of the organisation and are its driving force. The drivers will then take the products to the different charities, but The Lost Food Project encourages the charities to come by the warehouse and pick up food that they need and will use.

“We have to be careful who we give food to. We can’t give out food randomly. It’s a complicated jigsaw and we have to work out a clever but simple way of addressing this issue,” says Mooney.

The Lost Food Project currently works with 50 vetted charities in the Greater Kuala Lumpur area. A liaison is assigned to each charity to work closely with them, conducting occasional spot checks to make sure things are being done correctly.

SOLS Academy of Innovation, an educational non-profit organisation, has been picking up fresh fruits and vegetables from The Lost Food Project once a week for over a year. “It’s been a really great help to us and it makes the students happy to have a good meal,” says Saron Rous, the academy’s director.

The Lost Food Project also sends weekly food supplies to over 7,500 families in the People’s Housing Project and has set up kitchens in refugee schools. When food is provided at the schools, attendance rates shoot up.

Besides rescuing and supplying food, The Lost Food Project engages in education work and public awareness campaigns. At this year’s World Food Day in October, it ran a My Clean Plate challenge to encourage participants to finish their food and make a donation. The campaigns are to promote awareness around food waste and what we as individuals can do about it. Even simple changes, like eating leftovers and understanding expiry dates, can make a big difference in how much food gets thrown out.

“We’re not trying to be boring,” says Mooney. “We just want people to be thoughtful about food and to take baby steps toward changing their behaviour toward it. The more you get into food sustainability and wastage, the more you realise the massive impact it has on our planet.”

How You Can Help:

- The Lost Food Project needs volunteers to help with logistics, fundraising, marketing and more.

- A donation of just RM10 (USD2.40) provides 50 meals.